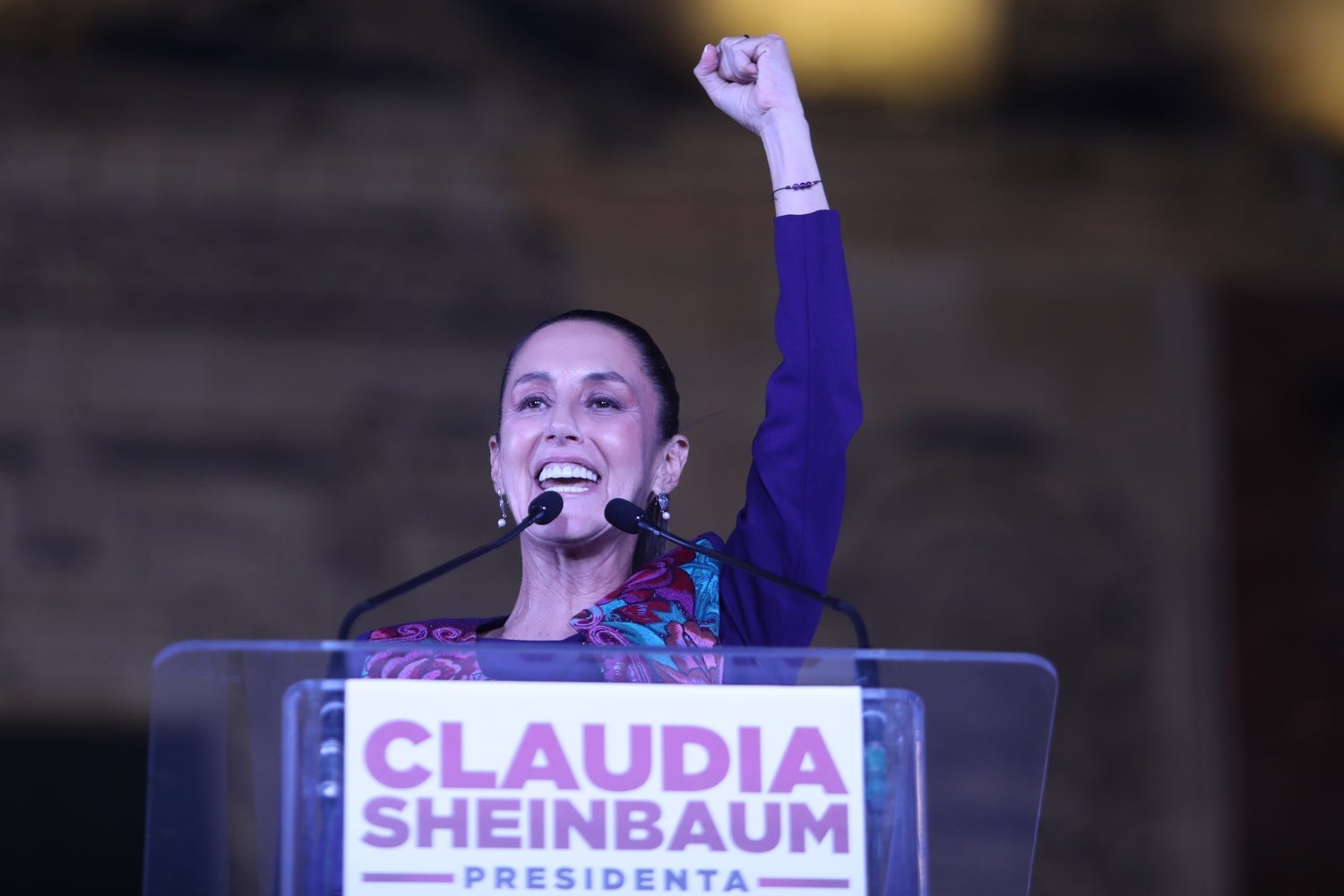

On June 2, Claudia Sheinbaum became the first woman and first Jewish person to be elected president of Mexico. But that’s not all: Sheinbaum is also a Nobel Prize–winning climate scientist. She has a Ph.D. in energy engineering and is the author of two books and more than 100 articles on sustainable energy and climate change. She helped pen the emission reduction sections of two Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports—including the flagship 2007 report that won the Nobel. Her election, however, is a reminder of the complexities and compromises that can arise when science meets politics.

Who is Claudia Sheinbaum?

Sheinbaum, who until last year was mayor of Mexico City, is a leftist with similar politics to Mexico’s current president and her longtime mentor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, although she has a greener thumb. Her campaign platform included a commitment to invest more than $13.6 billion in energy by 2030. The focus there is on renewable wind and solar, though her plan does include gas-burning power plants.

As president, Sheinbaum aims to “decarbonise the energy matrix as quickly as possible” and leave a legacy of energy transition, according to her 2024-2030 road map. But politics could get in the way of her mission. Mexico is a leading producer of oil, and this industry brought in 20% of government revenue in 2022. Sheinbaum pledged to support its state-owned oil company, Pemex, and maintain its production of 2 million barrels of oil a day, a political commitment some critics worry will limit the change she’s willing to make.

Scientists as elected officials

Some analysts are hopeful Sheinbaum’s election will propel a movement to get more scientists in office, but it’s important to remember politicians with scientific backgrounds aren’t inherently perfect. Sheinbaum herself infamously backed a 1,500-kilometer train corridor that cut through forests and archaeological sites. “I’m someone who makes decisions based on the data,” Sheinbaum told El Pais. Winning an election, though, is often the biggest test of that ideal.

In the U.S., a number of scientists have served in government recently, but more could be on the way. Seven Democrats with backgrounds ranging from biochemistry to computer programming were elected to Congress in 2018. The science-politics crossover makes intuitive sense; issues like climate change, pollution, abortion, and drug prices are scientific topics at their core. That’s one reason why some folks, like those at the nonprofit 3.14 Action, are recruiting and training scientists to run for office.