Editor’s note: Hello world-saving co-conspirators—Corinne here. It’s official: We just closed out the hottest summer ever recorded, one full of raging fires, deadly heat, and destructive storms. While most media outlets have been pointing out that a warming planet is the culprit more consistently than in years past, repeatedly making the link has to become the norm. Too many people aren’t connecting the dots, which is why I asked our newest one5c contributor, Molly Glick, to lay out those links in simple terms anyone can rattle off when faced with a skeptic. (Scroll on down to get into it.)

After all, speaking with one voice is what movements are made of. In fact, this week’s news digest includes two case studies on what collective action can accomplish—namely, spurring a steady decline in demand for gas and stomping out an invasive species. And, because un-trashing the world is something we all can do a little bit every day, we’ve also got your usual ration of energy- and waste-saving advice.

How are you liking the new one5c format? Shoot me a note at corinne@one5c.com anytime. And don’t forget to share us with your Earth-loving besties.

Swish: Gas-powered cars are going downhill

According to clean energy nonprofit RMI, we reached peak oil demand when it comes to cars—in 2019. Over the past four years, more efficient vehicles, including EVs, have cut the amount of petroleum we burn getting from A to B. By 2030, RMI predicts, the world will be reducing its thirst by 1 million barrels per day every year. That can’t come soon enough: At 27.2% of our country’s emissions, transportation is the largest slice of the U.S.’s pollution pie.

Easy energy saver: Let dishes air-dry

Of all the modern conveniences, the dishwasher is a special wonder. Technically speaking, it’s a robot (something that completes an automated task from start to finish) present in 80 million American homes. Although they’ve gotten much more efficient over the decades, one part of the wash cycle is still an energy hog: The “heated dry” setting is responsible for 11% of an appliance’s total greenhouse gas footprint over its lifetime. Many modern machines come with an easy fix: an air-dry mode that circulates room-temp air and uses way less juice.

Earth-friendly eats: What you really need to know about expiration dates

Food makes up a bigger portion of household trash than anything else in the U.S., and the dates stamped on many packages aren’t helping. Most of the time, they’re indicators of when vittles are at their highest quality, not a demarcation of when something’s no longer safe to eat. In the interest of keeping perfectly edible grub out of the bin, Cool Beans has pulled the best advice about the longevity of sustainable food staples—from tofu to dairy-free “dairy”—into one handy chart. You’re gonna wanna magnet this one to the fridge.

Good read: Why furniture got so bad

In the sustainability community, fast fashion is a common proof point for consumerism’s fallout. Rightly so: The popularity of brands like Shein and quickening pace of trends contributes to inhumane labor practices and literal mountains of trash, among other issues. Home furnishings, though, have been running on a parallel track for years. Last week, Washington Post reporter Rachel Kurzius dug into how we moved from cherished heirlooms to houses full of pressboard throwaway decor.

Cause for optimism: Death to lanternflies

It seems a yearslong campaign to literally squash invasive lanternflies might be working. Reports from Pennsylvania and New Jersey have tallied declining sightings of the uninvited and hungry guests, which have been outcompeting native species in more than a dozen states. Though success isn’t a certainty, the zeal with which the public has taken to stomping on the bugs is a hopeful sign for the power of simple collective action against an environmental foe. —Corinne Iozzio

5 weather myths, debunked in 100 words or less

There’s a disconnect in the ways people worry about weather. While most folks sweat extreme events like hurricanes, a recent Fast Company-Harris poll reports that concern about the climate crisis is less universal. In fact, around 1 in 10 people aren’t even sure there’s a connection between the two, according to a Yale and George Mason survey conducted this past spring. And that skepticism is magnified for people on the right side of the aisle; recent data from the University of Maryland and Washington Post says that only 35% of Republicans connect extreme weather events like severe storms and wildfires to a rapidly shifting climate.

The roots of doubt can spring from many places: fear, powerlessness, government distrust, or denial that the issue touches a person’s own doorstep. “Perhaps this is a coping strategy because it is so complicated and people feel very little agency to affect change,” says Dilshani Sarathchandra, an environmental sociologist at the University of Idaho and co-author of Inside the World of Climate Change Skeptics.

Communicating with these folks can be tricky. There’s no exact right way to convert a skeptic, and many might shrug off extreme events as normal. Clear explanations and hard data might help; and we’ve got lots of it, according to Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “We can put hard numbers on the effect of climate change on many different kinds of [weather] events,” he says.

For when you want to take a shot, we’ve turned that advice into a handy script you can use to rebut some of the most common extreme weather misconceptions. —Molly Glick

If they say: “Global warming? There are snowstorms in Los Angeles.”

You say: There sure are, and a lot of it is likely because of melting polar ice. When the Arctic gets more watery, it messes with something called the polar vortex, a band of winds that circle the North Pole and have long prevented chilly air from traveling too far south. As the temperature difference between the poles and hotter mid-latitude regions shrinks, it weakens the polar wind currents and drags them closer to the equator. So even Texans are no longer immune to winter cold snaps.

If they say: “Summer’s always hot.”

You say: Not this hot. Take July, which is typically the country’s warmest month of the year: The U.S. experienced an average July temp of 73.76 degrees Fahrenheit in 1923, and this past July the average jumped to 75.67 degrees Fahrenheit. Yes, that’s not even 2 degrees, but when you’re averaging the temps from 31 days, it takes an abnormal number of scorchers to move the average mercury. In fact, this was the warmest June to August worldwide since records began in 1940.

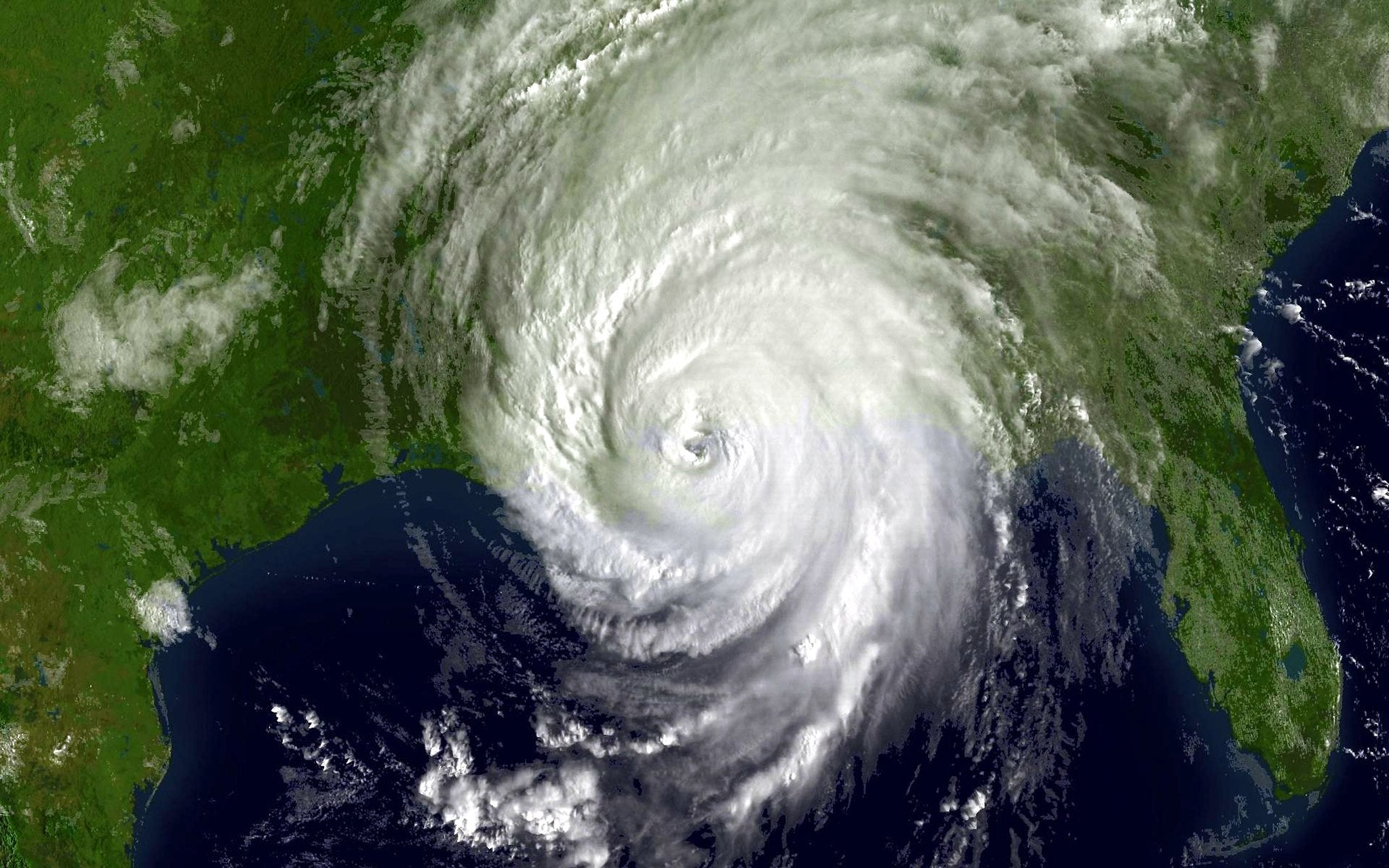

If they say: “Hurricanes are just a fact of life.”

You say: Sure, but they haven’t always been this bad. That’s because hotter air holds more moisture, around 7% more for every 1.8 degrees. Look at Hurricane Harvey: Analysis from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests the storm’s rainfall was at least 19% more than it would have been in cooler climes. Wind is getting worse, too: Hotter oceans warm the air, which help storms collect more energy as they travel to land. Rising seas also invite riskier storm surges, as happened with Hurricane Ian in 2022. All this adds up to bigger storms, even if there aren’t more of them.

If they say: “Trees naturally burn every few years.”

You say: Forests do need to burn to promote the growth of native plants, reduce the spread of pests, and send nutrients back into the soil. Indigenous populations around the globe have practiced controlled burns for thousands of years. But as the planet warms and dries, the scorched acreage has gone way up. The total U.S. forest area burned doubled between 1984 and 2015—beyond the expected amount from natural variability. That’s more than you can chalk up to mismanagement: When it’s hot and dry, plants lose more water to the atmosphere, and parched vegetation adds more (literal) fuel to the fire.

If they say: “It’s not weather, it’s a rogue experiment.”

You say: We simply don’t have the technology to conjure a storm. Humans have tried to manipulate large-scale weather events via a process called cloud seeding, but it hasn’t worked too well. Researchers have dropped chemicals like silver iodide into storms to try and weaken them. They’ve also failed to produce more than minuscule amounts of snow, so a full-blown hurricane is out of the question.