The billions of tons of food wasted around the world each year not only clog up landfills and contribute to climate change–inducing greenhouse emissions, but when you look at the stats on food waste, it’s easy to see where we can act to address food waste. Diving into the numbers gives us a window onto where the waste is happening, and also helps identify feasible solutions to this massive environmental and socioeconomic problem.

Before we dig in, a quick caveat on the numbers we’re about to run through: It’s difficult to nail down exact figures for food waste because not all companies, countries, and people report what they’re wasting (or do so accurately when they do). Differing definitions of food waste—for instance, whether or not the numbers include byproducts and scraps like potato skins and chicken bones—could also drastically change estimates, warns Pennsylvania State University professor Edward Jaenicke. “For me, it’s uneaten, human food,” he says, “but not everybody might think of it that way.”

Food waste around the world

Although exact numbers on the global food waste total are hard to pin down, experts commonly agree that at least one-third of the food available worldwide is lost to waste—measuring about 1.05 billion tons of grub worth about $1 trillion.1 Some organizations like the World Wildlife Fund say the total tonnage is even higher than that.2

Regardless, both estimates represent more than enough to feed billions of people, let alone sustain the more than 780 million people worldwide who go hungry.3 While those losses happen throughout the food supply chain, most of the food waste in the U.S. happens in households—after all the other resources used to produce the food (from farm land and water to energy and packaging) have already been gobbled up.

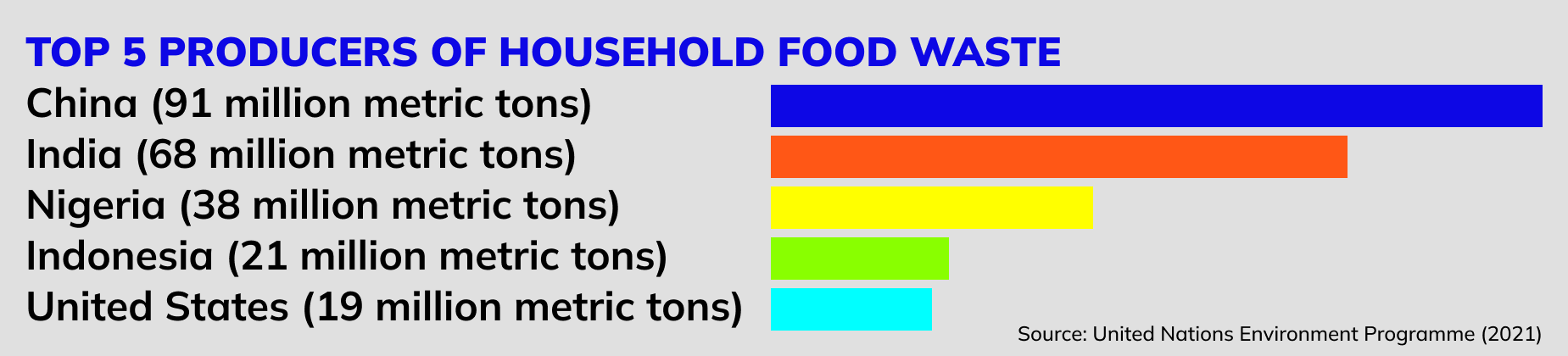

Which countries waste the most food?

Data published by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2021 shows that the most household food waste in the world in terms of sheer tonnage happens in China (91 million metric tons), India (68 million metric tons), Nigeria (38 million metric tons), Indonesia (21 million metric tons), and the United States (19 million metric tons).4 On an individual level, American food waste average about 400 pounds per person annually, or about 1,250 calories per day per person.5 However, those numbers only account for food waste at the household level, and data remains limited.

Global food waste on farms is around 1.3 billion tons annually. A 2021 report from the World Wildlife Fund and British supermarket chain Tesco estimated that total food waste lost “from farm to fork” is more than twice what has been previously calculated, at close to 2.75 billion tons annually. The report also notes that 58% of farm-based food waste occurs in high- and middle-income countries in Europe, North America, and Industrialized Asia.6

Which companies contribute the most to food waste?

Not all companies openly admit how much grub they’re tossing, but the biggest sectors responsible for food waste—aside from household consumers—are farms and manufacturing and food service industries. Across those three industries, a total of about 32 million tons of food got chucked in America in 2022 alone, according to ReFED, a national nonprofit focused on food waste solutions. A much smaller amount was wasted at the retail level that same year (about 3 million tons).7

Company-specific data is harder to come by. According to data and analytics company GlobalData, Nestle, Mondelez, General Mills, Hershey, and Danone led the corporate list when it came to generating waste of all kinds in 2021. Nestle generated about 790,000 metric tons of nonhazardous organic waste in 2021, according to the site, but it’s unclear how much of that specifically was food.

A 2018 press release from the Center for Biological Diversity said that 9 out of 10 of the biggest supermarket chains in the U.S. failed to report how much food they had been wasting. Since then, some of those retailers, such as Kroger, have publicly reported out food-waste numbers, says Ohio State University agricultural and environmental economics professor and food waste researcher Brian Roe.

Food waste in America

The worldwide trend of food waste is echoed in the U.S., where food waste adds up to about $240 billion annually.8 Looking at data from just over 4,000 households, Penn State’s Jaenicke co-author Yang Yu found that the average American household wastes about 31.9% of its food, and some of those homes were wasting well over 60% of what they were buying.9 They found that higher income families and smaller households had more waste.

“[Waste] at either the farm level and consumer level are definitely the two biggest parts in the U.S.,” Jaenicke says, noting that manufacturers are typically more efficient than individuals. Domestic producers also tend to be more efficient than those overseas, Jaenicke continues. Manufacturing operations in lesser-developed countries may suffer from less elaborate distribution or infrastructure, therefore producing more waste before hitting shelves.

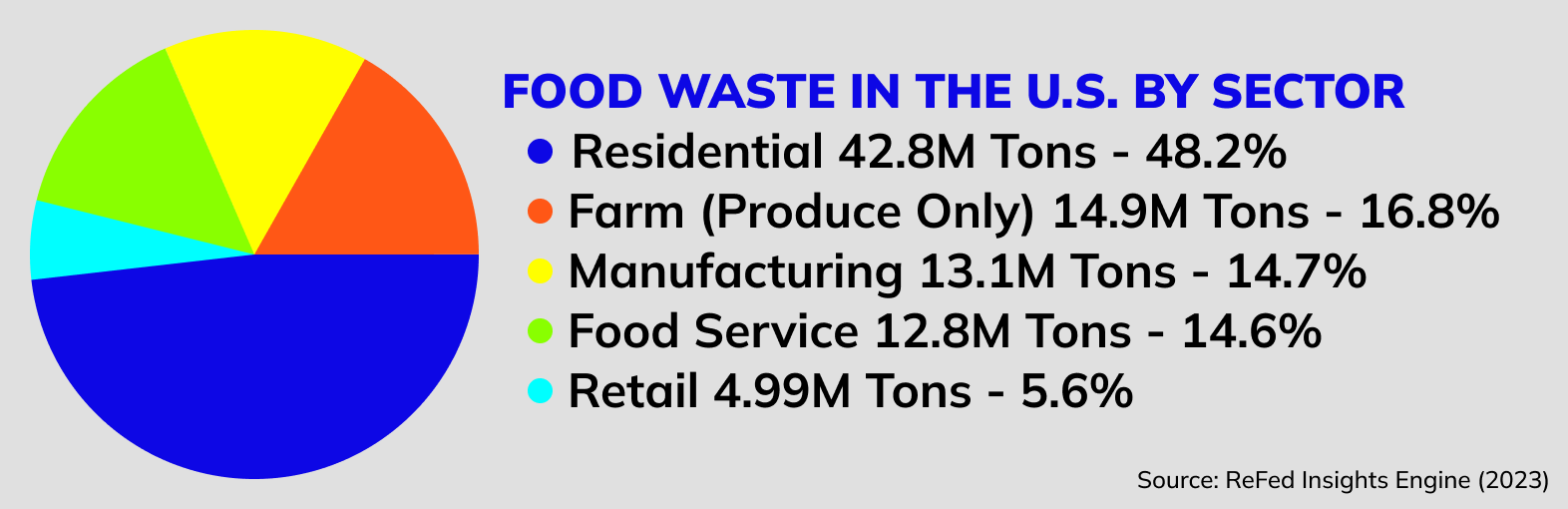

Food waste by sector in the U.S.

Though there’s waste in every step of the food supply chain, consumer waste is the largest piece of the pie. According to ReFED, about 42.8 million tons of food were discarded at the residential level in 2022. Farms saw an estimated food waste loss of about 14.9 million tons, though that figure only includes produce waste, not livestock or other animal agriculture. The food service industry discarded about 13 million tons, manufacturers chucked about 13.1 million tons, and retail accounted for another nearly 5 million tons of waste.10

Most commonly wasted foods in the U.S.

Across all sectors—from farm all the way to table—fresh fruits and veggies are the most commonly wasted grub in the United States, amassing some 31.3 million tons of waste. In fact, the total tonnage of tossed produce is almost equal to the second and third-most chucked foodstuffs (prepared food and dairy and eggs, respectively).11

What percentage of Americans are food insecure?

The amount of food wasted in the U.S. alone contains enough calories to feed those who are experiencing food insecurity. And then some. According to 2022 data, the USDA classifies 44 million Americans, including 13 million children, as “food insecure.” That amounts to 12.8% of all households in the U.S.—up from 10.2% the year prior.12 Food insecurity means living without consistent, dependable access to enough food to carry on an active, healthy lifestyle.

How much freshwater is used on wasted food?

Food production requires a lot of resources—land, energy, water. And, when upwards of 40% what’s made goes to waste, so too do the resources used along the way. According to the EPA, food waste in the U.S. alone squanders about 5.9 trillion gallons of clean water, which is the equivalent of the annual usage of 50 million American households.13

Sources and fates of food waste

Food waste happens at every step of the process. Sometimes it’s due to natural causes such as mold or bacteria. Other times it’s due to human error, such as misplaced orders, overestimated demand, poor storage facilities, and the drive to only have “perfect” produce. Misinterpreted sell-by dates can also play a role in consumers trashing food before it actually goes bad.14

Globally, about 14% of the world’s food is lost before it reaches retail markets, while another 17% percent (about 931 million tons) is lost at the retail and consumer levels, according to the United Nations.15 The majority of food waste happens at home. Even the least wasteful American households still toss about 9% of their food, says Jaenicke, according to his 2020 study results.16 “The idea of getting to zero is going to be pretty much impossible,” he says. “But we’re not talking about eliminating food waste—just trying to bring it down to a good, environmentally friendly level. Even if a household cannot avoid all waste, they can still keep it out of the landfill.”

Who in the U.S. creates the most food waste?

Jaenicke’s study is one of the first to adequately estimate losses at the household level. He and his co-authors used data from 4,000-plus households to connect certain characteristics—such as income levels and “dietary healthfulness”—to figure out the amount of food waste generated.

Among the biggest factors in determining the level of food waste are income and the size of a household. Those at higher income levels, the authors found, consistently waste more grub than those at lower levels. At the same time, households of one person ended up wasting around 20% more food than households of four or more. This is likely due to having fewer people available to eat leftovers and the challenge of having excess ingredients after cooking meals—for example, needing to buy a whole head of cauliflower for a dish, but not being able to eat it all.

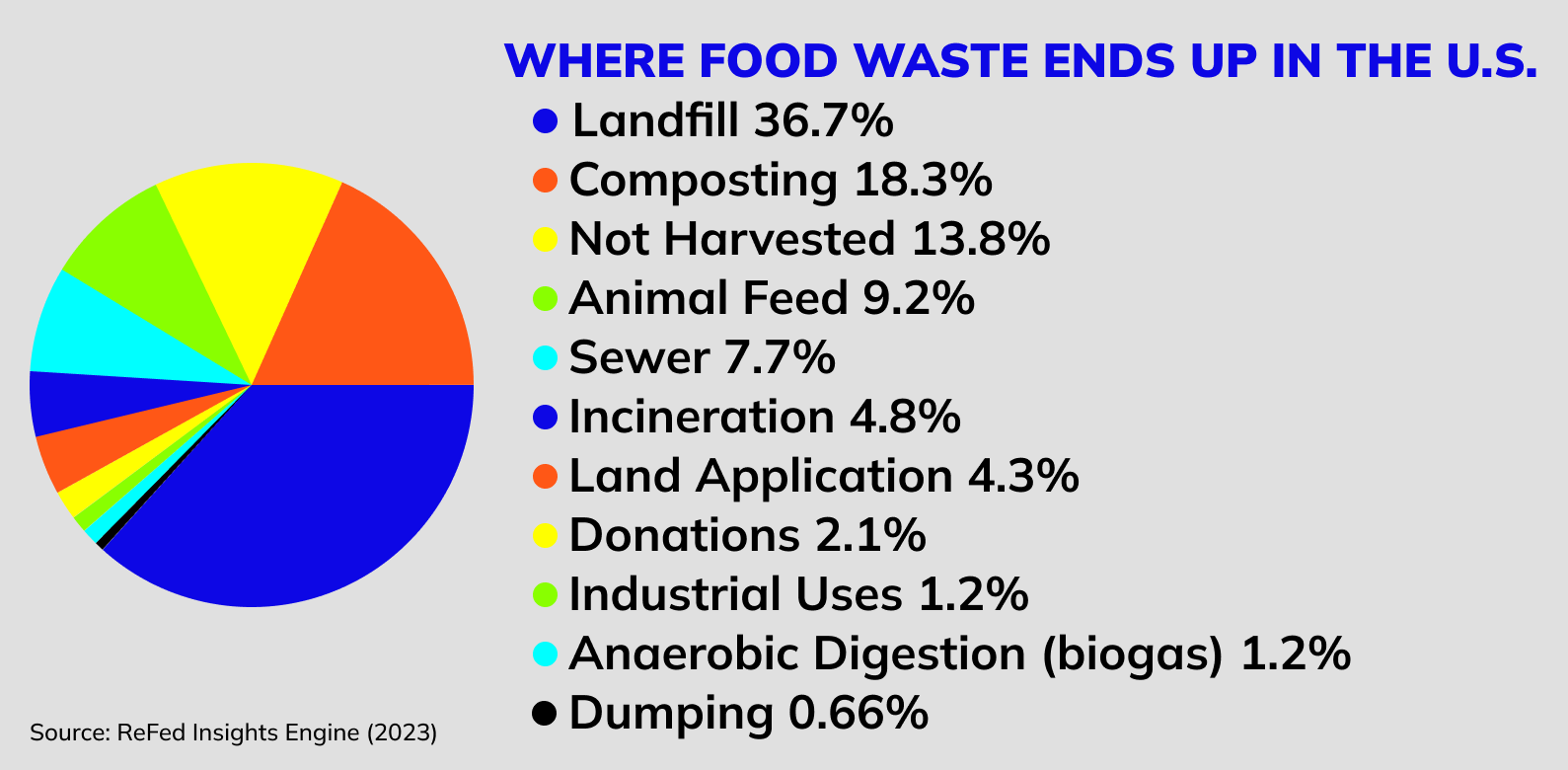

How much food waste goes to landfills?

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, about 63.1 million tons of food waste made its way to America’s landfills in 2018. Accounting for about 22% of the total landfill mass, food is among the most common material found in these trash heaps, the agency says. A majority of the methane emissions that escape from landfills is due to rotting food waste.

Five ways to recover food waste

From marketplaces that buy and sell excess food to more efficient production lines to consumer awareness, it doesn’t all have to be a loss. Here are a few forward-looking solutions for the proliferation of food waste.

Reduce food waste at home

For consumers, who waste by far the most food of any group, there are skills that can be developed to offset waste at the store and in the kitchen, explains Ohio State’s Roe. “My argument has been that consumer skill development is potentially the biggest impact, but probably the hardest to make happen because there are so many consumers with so many different stories at so many different levels,” he says.

“Consumer skill development is potentially the biggest impact, but probably the hardest to make happen because there are so many consumers with so many different stories at so many different levels.”

Brian roe, ohio state university

Condiment company Hellmann’s has even developed an app for that, which Roe calls one of the “most intriguing of the commercially based efforts to reduce food waste.” “Fridge Night” offers useful recipes based on the ingredients consumers already have at home.

Jaenicke and Roe both also caution that misleading food labels lead to waste. For the most part the dates on packaging are arbitrary and industry-led, with the exception of some food safety precautions like the labels on deli meats and soft, unpasteurized cheeses. It’s a confusing situation, Jaenicke says, and there are national advocacy efforts to unify date labeling systems in a more helpful way that focuses on food safety.

Using food waste to feed people

Diverting lost or wasted food at any step in the process to other people could offset the struggles of tens of millions of Americans who go hungry every day. Organizations like Feeding America partner with producers, manufacturers, and retailers to rescue some 4 billion pounds of potential food waste annually. Still, that’s just a fraction of the estimated 80 million tons of food that is wasted in America every year.

At home, people can help turn food waste into a solution by donating unused, unspoiled food to their local food banks, soup kitchens, and shelters.

Using food waste to feed animals

The EPA supports feeding scraps to animals as a way to handle food waste and divert it from the landfill. This can be done on the farm or at home for anyone who has snacking pets like dogs or backyard chickens (just keep in mind that some foods, like onions, aren’t safe for either). The federal agency even offers guidance on converting food waste into animal feed on a larger scale as well.

Turning food waste into energy

The conversion of food waste into biogas is also gaining traction. The idea is that systems can capture the methane produced by food waste-eating bacteria found in oxygen-poor conditions and use that gas to generate power. According to a 2023 Forbes article, dairy farms in several states have turned to the concept to handle both manure and food waste.

Composting

Composting food waste is far better than throwing it in the trash, in part because it diverts the waste from landfills where it could create methane. By composting our scraps and other food waste that we can’t use in a creative dish or donate, we can also improve soil quality in our gardens—where we’re hopefully growing our own veggies, too.

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2024, United Nations Environment Programme, Mar. 2024. ↩︎

- Driven to Waste: The Global Impact of Food Loss and Waste on Farms, World Wildlife Fund, Aug. 2021 ↩︎

- UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2024, United Nations Environment Programme, Mar. 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- The Estimated Amount, Value, and Calories of Postharvest Food Losses at the Retail and Consumer Levels in the United States, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Feb. 2014 ↩︎

- Driven to Waste: The Global Impact of Food Loss and Waste on Farms, World Wildlife Fund, Aug. 2021 ↩︎

- ReFED Insights Engine (2023), ReFED, Nov. 2023 ↩︎

- Estimating Food Waste as Household Production Inefficiency, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Jan. 2020 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- ReFED Insights Engine (2023), ReFED, Nov. 2023 ↩︎

- ReFED Insights Engine (2023), ReFED, Nov. 2023 ↩︎

- Household Food Security in the United States in 2022, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oct. 2023 ↩︎

- From Farm to Kitchen: The Environmental Impacts of U.S. Food Waste, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Nov. 2021 ↩︎

- The Effect of Sell-By Dates on Purchase Volume and Food Waste, Food Policy, Jan. 2021 ↩︎

- The State of Food and Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019 ↩︎

- Estimating Food Waste as Household Production Inefficiency, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Jan. 2020 ↩︎