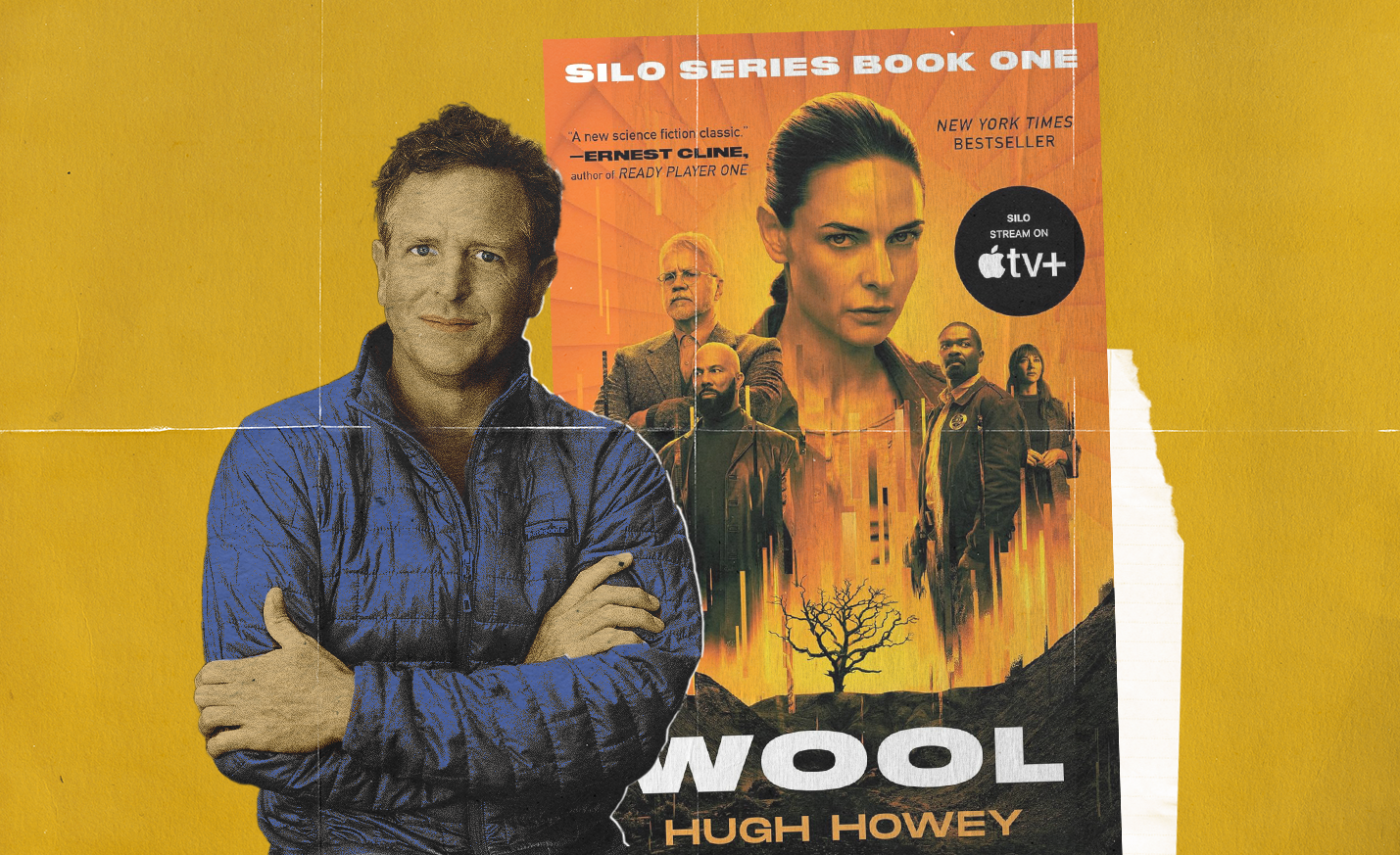

In the award-winning Silo trilogy, author Hugh Howey imagines a bleak future where what remains of humanity has survived for generations in a sealed underground world, the air outside is too toxic to breathe. For Howey, though, this dystopian vision—which has been adapted into a hit AppleTV+ series—is even more about hope than fear. The story centers on Juliette, a literal low-level mechanic-turned-sheriff, who starts to question the silo’s rules and her entire reality.

We sat down with Howey via Zoom to discuss the origins of Wool, the first book in the series, and chatted about his philosophy of dystopian storytelling, the modern parallels to the story, and the deeper commentary about media manipulation and government control. Howey also reflected on the Apple TV+ adaptation of Silo, and revealed the one major change he wished he’d thought of first. Premium Members can watch the entire conversation below—including Hugh’s reaction to seeing the Silo set for the first time and why community is so important—but here are some highlights, which have been lightly edited for length and clarity:

On the original inspiration behind Wool…

One of my first inspirations was the idea of Plato’s cave—the analogy from the Republic. Plato had this idea that we couldn’t see the true form of things; we were in a cave with a fire behind us, and all we could see were shadows on a wall. And he meant it metaphorically, but there’s a lot of literal reasons now that we know this to be true. Not only the limits of our visual and audio spectrum that we can perceive, but how our biases color what we see, and how our how we confabulate, how our brains aren’t as reliable as we think.

So, I was thinking a lot about that and noticing more and more that we were getting our view of the world through our screens. And this was before deep fakes were a thing, before fake news was a term, before AI and generated images and video. It was already not reliable to look at your screen and see what was out there, and that was something I wanted to explore. So, I came up with an idea of a civilization that’s having to think about the world through very limited access to information.

On the parallels between Wool and a real life climate diasester…

I’m always thinking about what’s going to cause an end to us, because it’s guaranteed. There’s no future in which humanity exists forever. The universe is either going to run out of energy or it’s going to stop expanding. It’s either going to be a big crunch or a heat death.

I think we should be considering all the different ways [the world] could end and try not to bring it about prematurely. Instead, we seem hell bent on hastening our own demise, instead of trying to maximize the time we have to flourish—and that’s pretty disheartening. That idea has been a central theme in science fiction for a long time. For many years, science fiction authors have lamented the idea that we would spend so much time and energy warring with each other, instead of trying to further our knowledge, our reach, and our horizons.

It’s so frustrating, for a lot of us, to see bombs being dropped instead of, say, building a space elevator. We’ve never tried. We have no idea. But it’s probably cheaper than any war we’ve fought—and all that gives us death and destruction.

On his main character’s strength and hopefulness…

I dedicated the book to those who dare to hope. You can’t write dystopian or apocalyptic stories without at least a little hope without disappointing the reader—otherwise, it’s just misery porn. What’s the point of a warning if you don’t believe people can hear it and find solutions?

For me, it’s all about the idea that things can be fixed. That’s Juliette’s defining characteristic: She sees things and assumes that they can be fixed. Her journey is learning that no machinery matters without people for it to sustain; she’s hyper-focused on [doing her job].

She’s up against people who don’t see that without a functioning society—which is kind of represented by the generator [that she maintains]—you can have the best intentions but no one’s going to survive. That tension between function and meaning is key to how we should think about organizing society. And I think that those two things are important to keep in mind as we try to think about how society should be organized. We need society to operate, but we need it to sustain a life worth living.

On striking a balance between dystopian portrayals of what could be and what still can be…

This really gets to the heart of how I think about environmental change. It’s tough to strike the right mix of action and optimism. If you’re too optimistic, you come off as naïve—like you’re not taking the issues seriously. It’s not “cool” to be hopeful, and sometimes the people who share your values will think you’re not doing enough.

On the flip side, if you’re too pessimistic, you risk giving up entirely—like, “What’s the point? We can’t fix this.” But the truth is, we’ve continually solved problems that once seemed impossible, and we’ve done it through hopeful action.

Take the hole in the ozone layer. That could’ve been a civilization-ending crisis if [the hole] had grown. Some people thought it was hopeless, but others said, “Let’s study it.” We found the cause—CFCs—realized there were alternatives, passed laws, and now it’s not even something we talk about much. It’s not as dramatic as outrage, but that kind of work gets results.

Defeatism doesn’t help anyone.

On the one Silo TV show change he wishes he made…

The one that stands out to me—and it feels so obvious now—is Walker. In the book, Walker is a man, and the character works a million times better as a woman. If I ever did a rewrite of the books, I’d change it so that new readers would meet Walker as we see her on screen. It just makes her more fiery, more relatable to Juliette—you really understand why Juliette found comfort in that space and in that relationship.

I love changes like that. I actually encouraged the showrunner and writers to deviate from the source material. I was the one always pushing them to make changes, and they were the ones pulling me back to the original story.