Hey team, and welcome back to one5c! I’ve been thinking a lot about “climate doom” lately, which is this thing where people acknowledge that we’re cooking the planet while also crapping on every solution. It’s all very “well, we’re screwed, so why try?” It’s one of my big hopes that our dispatches help remind y’all that we’ve got the tools we need to pull back from the climate crisis—even though they might contain a downer or two. All we’ve gotta do is embrace and use ’em. —Corinne

WHAT WE’RE INTO THIS WEEK

By Audrey Chan

Good question!

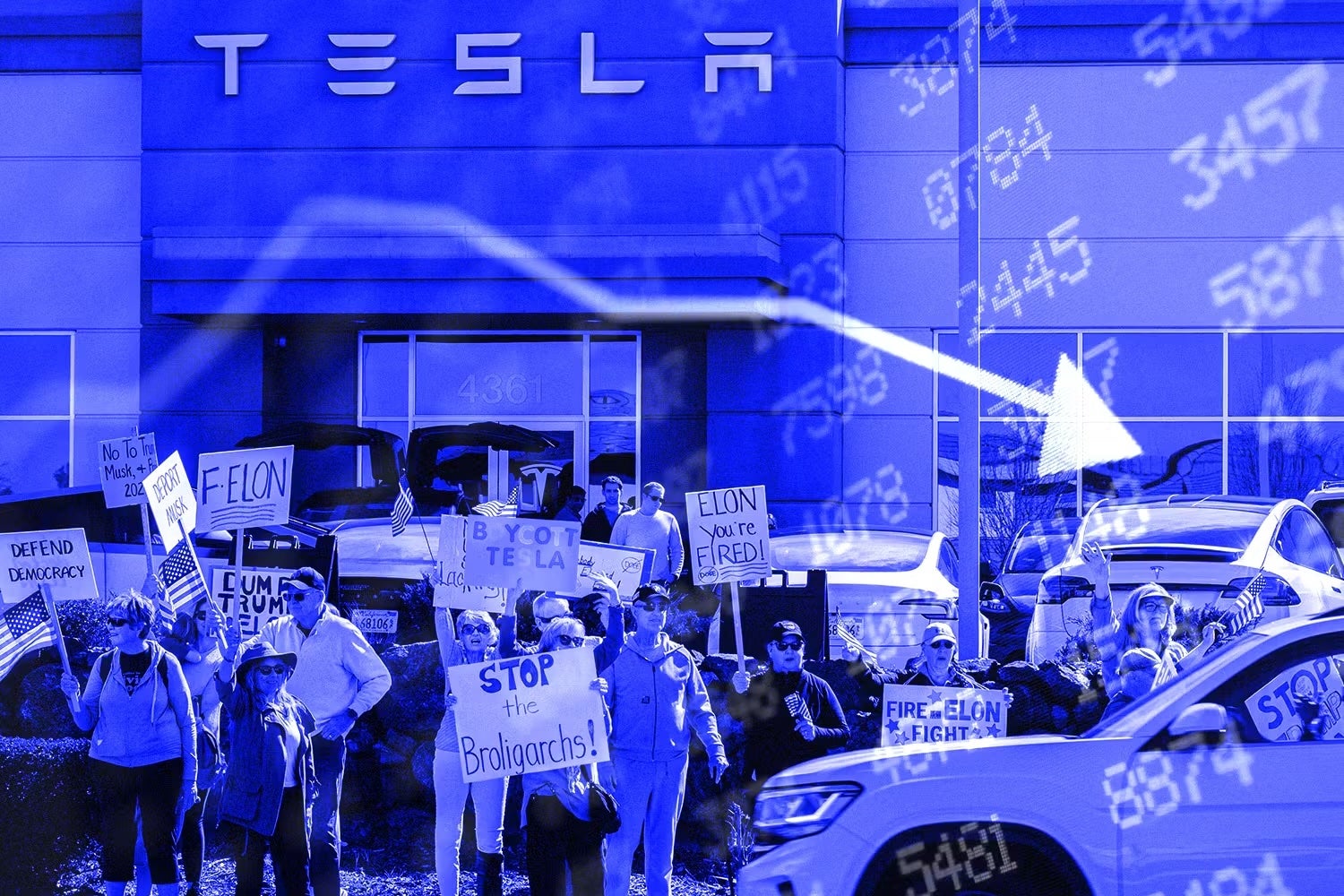

Could Tesla’s slide stall EV progress?

Tesla accounted for more than 40% of U.S. EV sales last year, but its brand image is taking a hit—and it might not be the only EV maker feeling the heat. Tesla is synonymous with electric whips for many Americans, William Roberts, a senior analyst at U.K.-based battery and EV research firm Rho Motion, tells Inside Climate News’ Dan Gearino. That means public backlash could push would-be EV buyers back into gas-powered cars. Tesla also plays a key role in EV charging stations, and most competing automakers have even adopted its North American Charging Standard. Still, Tesla’s slide doesn’t seem to be hindering global EV enthusiasm: In early 2025, global EV sales jumped 30% compared to the same time in 2024. Some see this as proof that the market is showing signs of resilience against Tesla’s troubles.

Listen to this

Canada’s most conservative province goes green

Edmonton, a city in the Canadian province of Alberta, is so associated with fossil fuels and the politics thereof that it’s sometimes called “the Texas of Canada.” (Its hockey team is even called the Oilers.) But Edmonton is also the site of Blatchford, a sustainable community taking shape on the grounds of a former municipal airport. The latest episode of the Volts podcast explores the project’s ambitions to create a walkable neighborhood that runs on 100% renewable energy and heats and cools buildings through what’s called a “district energy system”––which is a centralized network that acts like a heat pump for an entire neighborhood. Once completed in 2042, it’ll provide housing to 30,000 residents, with a density of up to four times that of its surrounding suburbs. Spanning roughly 1 square mile of centrally located land, Project Blatchford is also repurposing 93% of the former airport’s rubble for new buildings and crushing up the runways to pave new roads.

Study guide

Microplastics are messing with the food supply

Microplastics pollution could make it harder to feed the world, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The findings suggest these tiny plastic particles are messing with plants’ most important function: photosynthesis. Microplastics block sunlight, degrade soil health, and clog nutrient and water channels. All this could add up to a 12% drop in photosynthetic capabilities of land-based plants, potentially slashing up to 14% of the world’s staple crops of wheat, rice, and maize—which is on top of a 24-million-ton dip in seafood production every year due to microplastics. The researchers warn that unchecked plastic pollution could push another 400 million people worldwide toward starvation in the next two decades. “Importantly, these adverse effects are highly likely to extend from food security to planetary health,” the authors tell The Guardian, since plants play a major role in balancing Earth’s CO2 and mitigating climate change.

Report card

2024 was much more than the hottest year ever

Last week, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released its State of the Global Climate report. It confirmed, among a raft of findings, that 2024 was the hottest year in its 175-year observational history, with a global mean near-surface temperature roughly 1.55°C above the preindustrial average. Throughout the year, ocean heat reached its highest level in 65 years, sea-level rise surged to its highest point in nearly 30 years, and the world experienced 151 “unprecedented” extreme weather events. The report lays out plenty more sobering reality checks, but Celeste Saulo, WMO’s secretary-general, emphasizes they also serve as a wake-up call. “A single year above 1.5 °C of warming does not indicate that the long-term temperature goals of the Paris Agreement are out of reach,” she writes in the report.

MIC-DROP CLIMATE STAT

180–290 kg

The emissions associated with producing 1 kg of grass-fed beef, which is actually higher than for industrial beef, according to a new study. The range of other protein sources the authors looked at nets between 10 and 70 kg. Ready to wean off meat? Cool Beans serves up weekly recipes to help.

BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The skinny on ‘carbon-negative’ materials

By: Tyler Santora

Everything that goes into construction—from materials to the energy used to raise buildings—adds up to an estimated 39% of global carbon emissions. Energy-intensive materials like cement and steel make up a decent chunk of that pie. Already, some in the industry are reducing their footprint by using recycled or otherwise more sustainable stock, like bamboo or cork. Some of these supplies are even carbon-negative, meaning they hold on to more than what they emit.

With these strategies and more, a few carbon-negative buildings have hit the skylines. Some, like the Powerhouse Telemark office in Norway, rely on renewable energy generation to secure that status, while others have earned it through materials, like the Serpentine Pavilion at London’s Kensington Gardens. Even so, not all stock billed as “carbon-negative” is truly green.

What types of materials are carbon-negative?

Bio-based construction materials, like those used in the Serpentine Pavilion, are often carbon-negative because, well, they’re plants. When a material like bamboo grows, it captures CO2 from the atmosphere, which remains stored even if the bamboo is chopped down and used in a building—and it stays there as long as the structure stands. (This is the same reason, for example, that you want to mulch, not burn, a real Christmas tree.)

Some plant-based construction materials can even be superior to conventional products. The startup company Plantd, for example, uses fast-growing perennial grass to create panels that are stronger and more moisture-resistant than wood panels, and can be used in wall sheathing, roof decking, and subflooring. Hempcrete is made from hemp and lime and can be stacked in boxes around a structural (usually timber) frame, providing superior thermal insulation and moisture resistance compared to conventional materials.

Carbon-negative materials don’t have to be bio-based, though. For example, researchers recently figured out a method to make concrete components that sequester significant CO2. The procedure, described in a paper published in Advanced Sustainable Systems, involves running a current through electrodes placed in seawater and then injecting carbon dioxide scrubbed from the air. Chemical reactions between the CO2, water, and natural dissolved minerals create solid minerals, including calcium carbonate (a carbon sink) and magnesium hydroxide (which further reacts with CO2 to sequester more carbon). These materials can hold more than half their weight in carbon.

The minerals could then be used as a substitute for sandlike aggregate that’s in heavy demand in construction, particularly for concrete and cement. By altering factors like voltage, the researchers can precisely control the properties of the minerals they make, allowing them to craft the ideal aggregate to be used in a range of materials.

Warning: Potential for greenwashing ahead

Not all products branded as carbon-negative are truly green. Timber is perhaps the worst offender. Sure, like all plant-based materials, wood stores carbon. But each tree would sequester more carbon if it were still in the ground—not to mention it would benefit the environment in other ways, like as habitat and food for critters. Companies like ThinkWood are pushing timber as a carbon-negative material, but research shows that so-called “mass timber” could emit even more carbon than steel or concrete. Other biomaterials don’t necessarily have the same problem, particularly when they grow a lot faster than trees.

Building new structures with carbon-negative materials—assuming they’re legit as opposed to greenwashing—is also no substitute for using what’s already standing. Retrofitting an existing structure rather than building anew comes out ahead in almost all instances, according to an analysis published in fall 2024. The emissions that went into getting existing steel or timber or concrete where it is, coupled with how much energy demolition and rebuilding takes, makes the math kinda easy.