Hey team, and welcome back to one5c! I complain (a lot) about the New York City subway system, but I’m allowed. You know the rule about how no one’s allowed to dunk on your family except the people in your family? The same thing applies to your mass transit system—if you’re fortunate enough to live in a place that has one. I’ll whine and moan about delays, stank cars, or stations so hot I’m sure they were in Dante’s inferno, but if someone comes at the subway who doesn’t ride the damned subway? We’re gonna have issues.

Last week, New York’s governor torpedoed congestion pricing, a tolling system that would funnel $1 billion a year into updating the sprawling train network that quite literally keeps the city running. I was pissed. I’m gonna be pissed for a long time. But as I sat at my desk steaming, I heard something from the other room: It was my partner calling our representatives to register his immense displeasure with the decision. He’d turned his rage into action, which is all most of us can hope to do in a moment like that. For the record, I’m still pissed, but also a little inspired. —Corinne

WHAT WE’RE INTO THIS WEEK

By Shreya Agrawal

Good read

Mothers bear the brunt of the climate crisis

The climate crisis will affect every person on the planet, but women and gender minorities will be more vulnerable. This is especially true for expectant mothers, who are particularly endangered by more extreme heat and other environmental changes. We’re only just beginning to understand all the ways a heating world can impact reproductive health. This four-part series, a collaboration between Grist and Vox, explores the unexpected risks a group of women face before, during, and after pregnancy. Each story weaves tragedy and hope with the reminder that safeguarding the future for mothers and their children can come through systematic change.

Watch this

What folks get wrong about the energy transition

Replacing fossil fuels with renewables can seem quite impossible if you consider that about 80% of global energy comes from burning dead dinosaurs. But this excellent new explainer from Adam Baheej Adada, a reporter with German news outlet DW, delivers a salve for fears that we’ll never be able to generate enough electrons from the sun and the wind. The key point: We slurp up a lot of electricity because we’re not smart enough about how we use it—no matter where it comes from. Compared with machines like gas-powered cars and furnaces, electric gadgets are more efficient at how they use energy. “If we can replace half our current energy use with energy efficiency and the other half with renewables, then it looks a whole lot easier,” said Nick Eyre, energy expert at University of Oxford.

Accountability check

A local climate reversal with ripple effects

Last week, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul decided to delay congestion pricing policies in New York City, citing “affordability and cost of living” concerns for New Yorkers. Congestion pricing helps reduce traffic on the streets during peak hours and encourages more people to use public transit, reducing emissions and pollution. Similar tolling systems have been successful in cities like London, Stockholm, and Singapore, and New York was set to be the standard-bearer for bringing it to U.S. cities. For those reasons (and more) Hochul’s decision will go down as one of the worst climate fumbles from a Democrat ever, writes Robinson Meyer of Heatmap News. At least transit advocates say they’re not done fighting.

Study guide

Putting emissions on ice

Almost one-third of the food we produce goes to waste. But, according to a recent study in Environmental Research Letters, a significant amount of emissions associated with uneaten edibles can be avoided simply through better refrigeration. Improving “cold” supply chains, especially in nonindustrialized regions like Southeast Asia and Africa, could prevent around 50% of food loss—that’s grub that never even makes it to the store or market—and avoid more than 800 million tons of emissions. That’s more than the annual greenhouse gas footprint of Germany. Setting up refrigeration systems might not be feasible everywhere, the authors note, but keeping supply chains short can also cut emissions associated with good grub going bad.

MIC-DROP CLIMATE STAT

64%

The portion of companies who’ve made promises about adopting regenerative agriculture, but don’t have anything in place to make good on them. Check out our guide to this new food buzzword.

WHO’S WHO

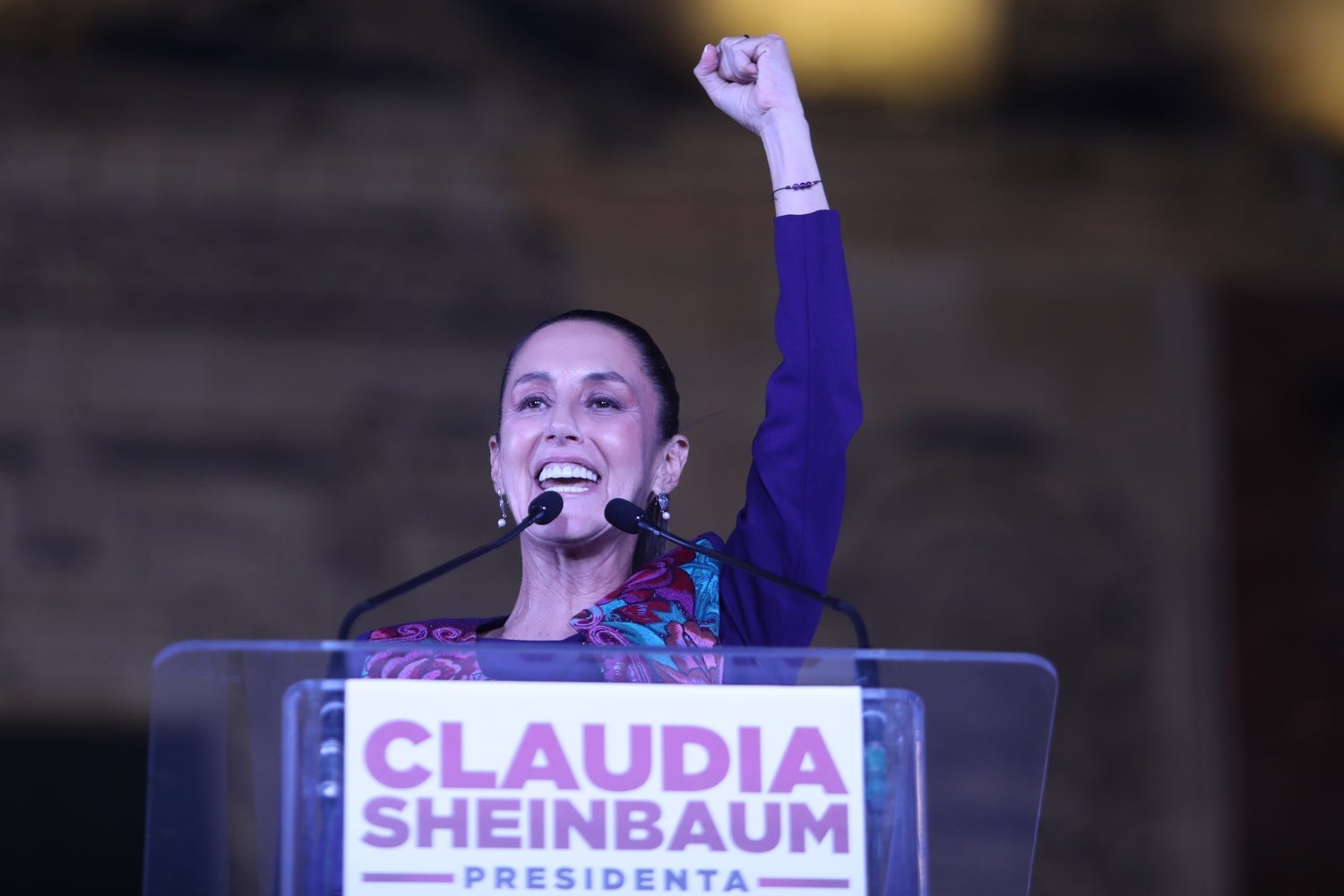

Meet Claudia Sheinbaum, the climate scientist about to run Mexico

By Tyler Santora

On June 2, Claudia Sheinbaum became the first woman and first Jewish person to be elected president of Mexico. But that’s not all: Sheinbaum is also a Nobel Prize–winning climate scientist. She has a Ph.D. in energy engineering and is the author of two books and more than 100 articles on sustainable energy and climate change. She helped pen the emission reduction sections of two Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports—including the flagship 2007 report that won the Nobel. Her election, however, is a reminder of the complexities and compromises that can arise when science meets politics.

Who is Claudia Sheinbaum?

Sheinbaum, who until last year was mayor of Mexico City, is a leftist with similar politics to Mexico’s current president and her longtime mentor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, although she has a greener thumb. Her campaign platform included a commitment to invest more than $13.6 billion in energy by 2030. The focus there is on renewable wind and solar, though her plan does include gas-burning power plants.

As president, Sheinbaum aims to “decarbonise the energy matrix as quickly as possible” and leave a legacy of energy transition, according to her 2024-2030 road map. But politics could get in the way of her mission. Mexico is a leading producer of oil, and this industry brought in 20% of government revenue in 2022. Sheinbaum pledged to support its state-owned oil company, Pemex, and maintain its production of 2 million barrels of oil a day, a political commitment some critics worry will limit the change she’s willing to make.

Scientists as elected officials

Some analysts are hopeful Sheinbaum’s election will propel a movement to get more scientists in office, but it’s important to remember politicians with scientific backgrounds aren’t inherently perfect. Sheinbaum herself infamously backed a 1,500-kilometer train corridor that cut through forests and archaeological sites. “I’m someone who makes decisions based on the data,” Sheinbaum told El Pais. Winning an election, though, is often the biggest test of that ideal.

In the U.S., a number of scientists have served in government recently, but more could be on the way. Seven Democrats with backgrounds ranging from biochemistry to computer programming were elected to Congress in 2018. The science-politics crossover makes intuitive sense; issues like climate change, pollution, abortion, and drug prices are scientific topics at their core. That’s one reason why some folks, like those at the nonprofit 3.14 Action, are recruiting and training scientists to run for office.