Hey team, and welcome back to one5c! When we put out calls for new writers and editors to join us at one5c, one thing we always ask for is people who identify as “human BS detectors.” Climate is a subject matter ripe for bending the truth about the planet-warming potential of all manner of things, from policies to products, so a big part of being a climate-conscious individual is understanding and spotting those untruths.

This week our BS sirens lit up a bit more than usual. After the digest, Tyler’s got the scoop on a newly popular policy philosophy called “climate realism” (spoiler: it’s kinda climate doom in disguise), but first Audrey wants to tell y’all about Big Beef’s latest greenwashing blunder. —Corinne

WHAT WE’RE INTO THIS WEEK

By Audrey Chan

Consume this

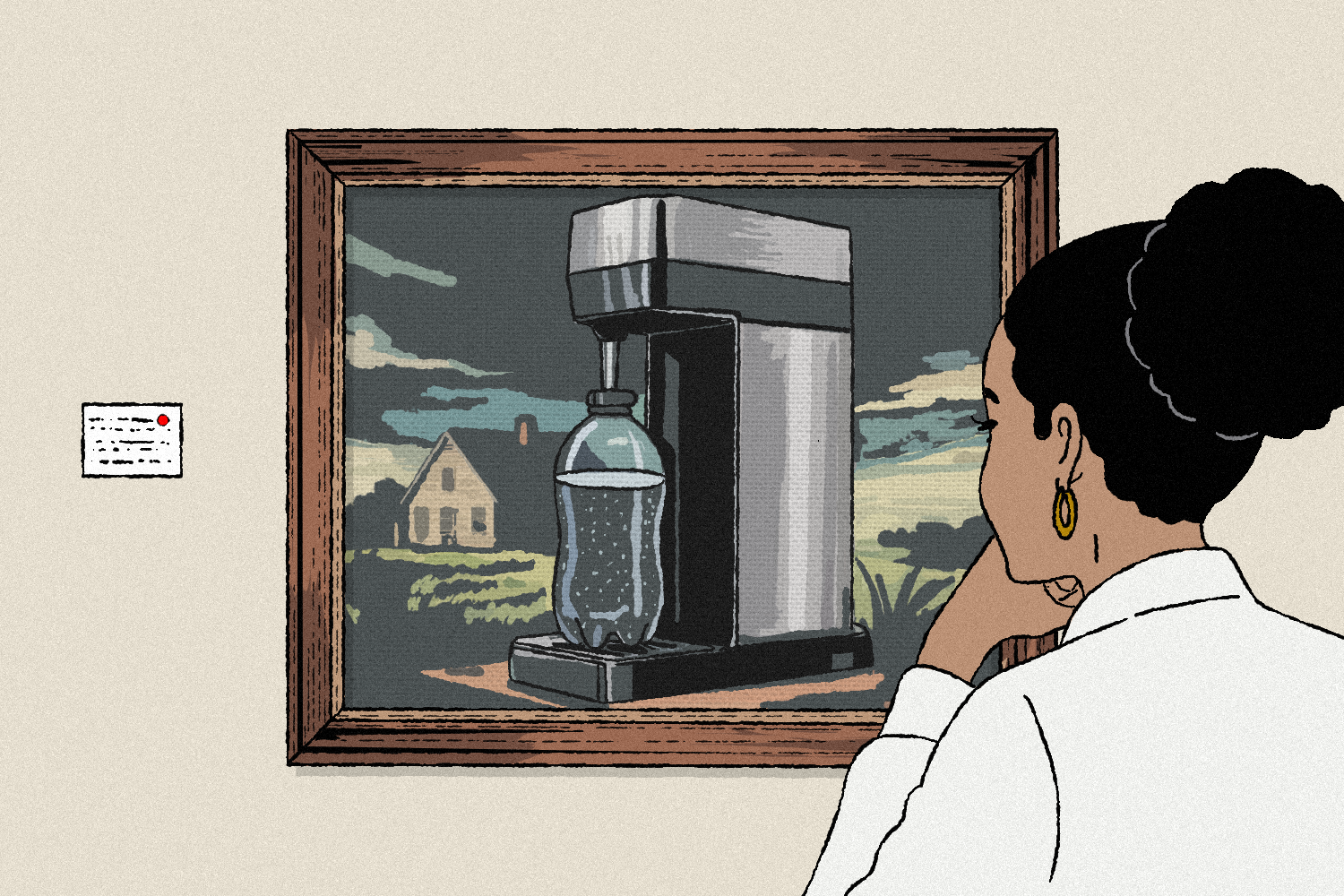

The best soda maker

Americans love their fizzy drinks: The average person in the U.S. guzzles 42.2 gallons of soda a year, and North America as a whole is expected to down 35% of all the world’s fizzy water by 2028. For seltzer enthusiasts, an at-home soda maker offers a convenient, cost-effective, and planet-friendly alternative to getting that bubbly fix. Sure, the machines cut down on single-use plastic, but they also slash transportation heft: One of the CO2 canisters a soda maker uses weighs 5.7 pounds and makes up to 60 liters of bubbly water, while a 12-pack of seltzer weighs 9.8 pounds for just 4.2 liters. We gave four popular models a spin—assessing ease of use, carbonation, bubble longevity, taste, and sustainability of each brand’s business practices. The official one5c pick satisfied our thirst for good design, consistent fizz, and crisp taste. Bonus: The company sends free spare parts upon request. Check it out here.

Greenwatch

Big Beef fumbles its promises (again)

Beef production is the leading driver of deforestation—which could push the Amazon close to a tipping point that turns it from a carbon sink into a carbon source. The Brazil-headquartered giant JBS—the world’s largest meat producer—has promised to clean up its Amazon supply chain by the end of 2025. The company launched a network of “green offices” to help ranchers comply with new rules, including plans to plant more trees, withdraw from contested territory, and outfit cattle with ear tags. But ranchers and unions in Brazil tell The Guardian that the deadline is “impossible,” pointing to technical barriers, land disputes, and lack of government support. Some even admitted to “cattle laundering”—a loophole that involves slaughtering cattle in unregulated areas before selling the meat. This all comes after New York Attorney General Letitia James sued the company for misleading consumers with its climate goals to increase sales. At the end of the day, though, the best thing anyone can do for the Earth is skip the beef altogether.

Cause for optimism

The first global emissions tax

If the maritime industry were a country, it would rank sixth in terms of carbon emissions. Last week, 63 member states of the U.N.’s International Maritime Organization (IMO) agreed to implement emission caps and a carbon tax across the entire sector. The measures, set to be adopted in October and go into effect in 2027, will become mandatory for ships weighing more than 5,000 tons, which account for 85% of international shipping’s total emissions. The global framework is a huge first step toward the IMO’s ultimate goal of a net-zero shipping industry by 2050. But the deal has some obstacles: The U.S. pulled out of the talks before they happened, threatening to reciprocate against any fees imposed on American ships; petrostates including Saudi Arabia and Russia have also opposed the deal; and some island nations worry it’ll place an unfair burden on developing economies. All the while, environmental groups are also demanding stricter targets.

Study guide

Climate change is making rice less nice

Half of the world depends on rice—but human-caused climate change could turn this staple into a hazard. A new study published in The Lancet reveals rising temperatures and CO2 are increasing arsenic levels in rice. Plant physiologists studied rice crops from 2014 to 2023 to simulate future climate conditions and found that as heat and emissions rise, so does the toxin. Arsenic occurs naturally in water, soils, and foods like fish, but inorganic arsenic—which, among other issues, is linked to skin, lung, and bladder cancers and heart disease—stems from industrial materials. Rice is a highly porous and thirsty grain, which makes it apt to soak up any surrounding arsenic, especially risky in industrial regions like those near old landfills and ore mines. This doesn’t mean everyone should stop eating rice right now, the authors tell Grist; current levels are higher than in other plants, but still low overall. Rather, these results are a wake-up call. Despite years of warnings, the FDA has never set limits for arsenic in foods. The authors suggest developing strains of rice that are less absorbent and educating consumers about rice alternatives.

MIC-DROP CLIMATE STAT

250 pounds

The amount of raw minerals it takes to create one new smartphone, according to device-repair specialist iFixit. Looming tariffs have spurred some companies to urge customers to upgrade now. But the better plan is to extend the life of the device you’ve already got. Here’s how.

What’s that?

‘Climate realism,’ a buzzy new philosophy, is just doom in disguise

By Tyler Santora

Earlier this month, the Council on Foreign Relations—an influential, nonpartisan think tank—launched the Climate Realism Initiative. The initiative will provide recommendations to the U.S. government for climate change policies and develop strategies to win the global clean energy tech race. Sounds great, right? Alas, its potential benefit for the planet isn’t so realistic.

According to career experts in climate science and policy, the concept of climate realism is little more than an evolution of climate doom, which in itself is an evolution of climate denial: It accepts the realities of human-caused warming but abandons hope of limiting the uptick to 1.5 degrees C or even 2 degrees C this century.

Realism could be used to undergird policy that values the American economy over cutting emissions, which could lead to, say, the continued use of fossil fuels rather than a full switch to green energy. “If [realism] is about facing hard truths and calling out political delay, then yes, it can serve a purpose,” says Sam Illingworth, a science communication expert at Edinburgh Napier University in Scotland with a background in atmospheric science. “The problem is when ‘realism’ becomes a synonym for resignation.”

Here’s what you need to know about the buzzy new philosophy—and a few alternative approaches that might serve us better in the actual climate reality to come.

What is climate realism?

There are three tenets of the climate realism doctrine: 1) Prepare for a world that blows through its climate targets; 2) invest in globally competitive clean technology; 3) lead international efforts to avert truly catastrophic climate change. None of these are terrible at face value. But the devil, as they say, is in the details.

The biggest problem with climate realism is that it accepts that the world is going to blow past 3 degrees C of warming this century, says Jason Thistlethwaite, a professor for the School of Environment, Enterprise and Development at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Even business-as-usual forecasts aren’t that grim, putting us closer to 2.6 degrees C. Thistlethwaite points out that, even without policy change, renewable energy will continue to grow, limiting warming, because of how cheap it has become. “[Realism is] doomerism, and it doesn’t serve a useful purpose to think that there’s nothing we can do about our existing emissions trajectories,” Thistlethwaite says. “It’s disempowering.”

Realism also holds that American emissions are small in the global picture, which means other nations should invest in reducing theirs—not the U.S. (The U.S. ranks second, behind China, in terms of total greenhouse-gas output.) This POV penalizes countries whose emissions are on the rise, including developing nations, to protect the U.S. from warming-fueled impacts like extreme weather. Although this could be effective, it obscures the fact that developing nations face the most danger from climate change.

Some parts of climate realism do have the right idea, says Thistlethwaite. For example, it says that instead of leaning into solar, a clean energy area that China dominates, the U.S. should be focusing more on tech it can own, like geothermal and nuclear. Realism holds that American dollars should be spent in climate resilience such as seawalls, drought-resistant crops, and heat wave action plans. But, he adds, none of that should come at the cost of abandoning mitigation.

If climate realism isn’t the right framing for attacking the climate crisis, then what is? We asked Illingworth, and he offered up three:

First is the philosophy of climate pragmatism, which recognizes the severity of the crisis, while highlighting the impact of policy change that takes root in collective action. Examples of this in the real world? Bans on short-haul flights in France, electric vehicle incentives in Norway, and emissions reductions from building efficiency in South Korea. “People will support bold policies if they are fair and viable,” Illingworth says.

Second is climate justice, which centers on equity and solutions for populations who disproportionately experience the negative impacts of human-caused warming. Lastly is the idea of climate empowerment, which is an everyone-at-the-table approach adopted by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that Illingworth says focuses “on how communities can build resilience, push for better infrastructure, and drive the cultural shift that real change requires.”