Happy Monday, and welcome back to one5c. After a September marked by extreme weather and “gobsmackingly bananas” heat, we’re continuing to monitor signs of progress. Analysts are eyeing the peak of fossil-fuel emissions, folks are largely coming around to having wind farms in their neighborhoods, and a Swift romance has brought renewed attention to the climate costs of celebs’ private jet habits. And, because dealing with our oily woes is about more than the carbon that gets belched into the sky, we’re taking a look at a new setup that promises to corral plastic before it spills into the ocean.

If you’re digging these stories—and one5c in general—please spread the word.

Lessons in misdirection: For Taylor Swift, is a Jet also a jet?

By the end of last week, Taylor Swift’s appearance at the Chiefs-Jets game to root on new beau Travis Kelce birthed an unexpected internet theory: that the megastar was gaming Google search results for the phrase “taylor swift jet” to push a wave of stories about the footprint of her private flights out of the top spots. If this is a PR master class, it may be backfiring. It’s reminding folks that super-celebs’ personal aircraft are massive emitters, and T-Swift is the worst offender. One analysis found that the miles logged by her aircraft in 2022 produced 8,293.54 metric tons of emissions—1,184.8 times the average person’s annual total. Sure, anyone who flies has to contend with the outsized impact of those trips, but the footprint of the mega-rich remains pretty darn hard to justify.

Good read: How to build a heatproof city

There’s an odd paradox in our cities. Dense population centers keep acreage outside the urban core available as carbon sinks and for agriculture, but the way our current metropolises are built creates and traps heat—making temps in the center of town consistently around 7 degrees hotter than in the surrounding areas. Grist has drawn up plans for a future city armed with the technologies and infrastructure changes to avoid that problem, and more. Their 360-degree panorama features 18 potentially transformative enhancements to commercial, residential, and civic centers.

Cause for optimism: Eyeing the peak of fossil fuel emissions

There’s a ton to unpack in the International Energy Agency’s new Net-Zero Roadmap, which includes a list of to-dos for speeding up the adoption and rollout of existing energy technologies like green hydrogen and renewables. The IEA’s models, though, also include some handy encouragement—most notably the fact that fossil-fuel emissions will peak in 2025. The data also mirrors a new analysis from Ember, a clean-energy think tank, which shows that emissions from burning dead dinosaurs went up only 0.2% in the first half of this year.

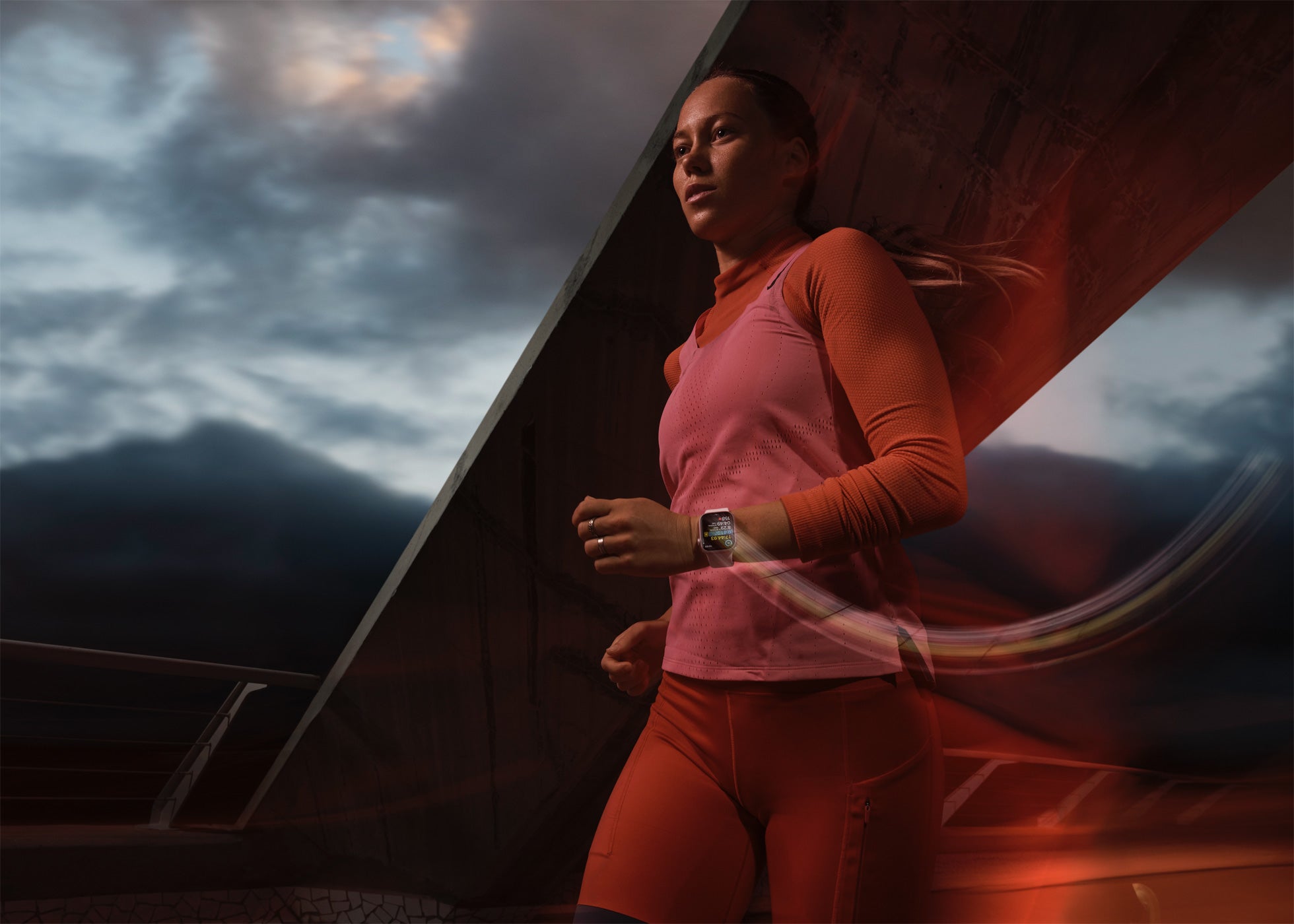

Is it greenwash? Inside Apple’s ‘carbon-neutral’ watch

When Apple announced its newest Watch in mid-September, there was much ballyhoo about the digital timepiece’s complete lack of climate impact. The claim of carbon neutrality raised an alarm at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), a nonprofit research firm based in Beijing. As reported by Inside Climate News, IPE’s assessment on the claim amounts to a deeply skeptical eyebrow raise. The report points out a lack of transparency in how much (or little?) Apple’s suppliers tap renewable energy sources in their manufacturing processes. Fair’s fair, though: The company has made consistent gains in reducing the impact of its entire product line, but claims of neutrality are likely overblown.

Mic-drop climate stat

69%: The portion of people in the U.S. who say they’d be totally fine living near a wind farm, according to a recent Washington Post-University of Maryland poll. About 75% would be OK close to a solar array. The results buck the not-in-my-backyard sentiment commonly trotted out when talking about renewable infrastructure.

Works for progress: A new trash-catcher for ocean plastic

By Anna Kramer

Eight million tons of plastic enter the oceans every year, threatening marine life and breaking down into microplastics that work their way into the food chain. But the biggest sources might not be what you’d expect. More than one-third of that rubbish comes from rivers, and more than 80% of that (or around 2.4 million tons) flows from a fraction of the world’s waterways, according to a 2021 study in the journal Science Advances. Small countries with relatively large coastlines and a lot of rainfall tend to push the most plastic waste into the ocean. Guatemala, for example, is about the same size as Tennessee and sits at No. 15 on the list of nations whose rivers contribute to ocean plastic waste, according to the same study.

That’s why The Ocean Cleanup—a nonprofit group that has pledged to try to remove the plastic from the world’s oceans and top 1,000 polluting rivers—has zeroed in on the Rio Las Vacas near Guatemala City, which it estimates contributes 2%-3% of all ocean plastic. The group’s efforts there, based on a new system of floating barriers called the Interceptor Barricade, represent one of 11 river-cleaning projects in seven countries it has underway. And it could stand as a model for similar waterway interventions around the globe.

How it works

In Guatemala, many of the problems that lead to outsized plastic pollution have coalesced at once. Fast population growth and development of Guatemala City have outpaced investment in waste management and sanitation infrastructure. Some companies and people illegally dump trash into the river. And seasonal rains between May and October cause regular flash floods to rush plastic through the Rio Las Vacas, out into the larger Rio Motagua, and into the Caribbean Sea.

The Barricade is The Ocean Cleanup’s second attempt at stemming the flow from Rio Las Vacas. In 2022, the group installed a fence, bolted to the river floor, to capture the plastic while still allowing water to pass through. But under the weight of the waste and the pressure of the water, the fence pulled out of its bindings during one of the first major floods.

In May 2023, the group tried a second time with a different structure. It installed a pair of heavy floating booms at two points along the river and chained them to dry land on either side of the waterway. So far, the rig has worked: The booms collected 140 tons of trash in one flood in September, another 500 tons in a previous flood in August, and hundreds more from floods earlier in the year—all while allowing water to flow underneath.

The road ahead

Environmental advocates have mixed feelings about The Ocean Cleanup’s efforts, but its work to corral plastic in rivers is less controversial than projects aimed at removing it from the open ocean. The one that’s drawn the most scrutiny is aimed at the most infamous site of plastic pollution: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The issues, marine researchers say, are threefold: Removal is probably more disruptive to wildlife than leaving the trash alone; dredging leaves behind smaller and more dangerous microplastics that sit below the surface; and the ferrying of trash out of the site creates carbon emissions.

By comparison, stopping plastic before it can make it to the ocean is less resource intensive and significantly less disruptive to wildlife, and it prevents junk from lingering and breaking down into smaller and more difficult-to-grab pieces. The Ocean Cleanup hasn’t specified other rivers where this same system could work, but the success of the Barricade may be a hopeful sign for fast-moving or flood-prone waterways similar to the Rio Las Vacas.

Even with setups like the Barricade in place, however, researchers and environmental advocates agree that we should be treating the problem and not the symptom. The single best way to address plastic pollution is to reduce production, consumption, and waste. Taking plastics out of the ocean will never match the flow of plastic into it as long as human consumption continues at the same rate or increases.

In that respect, the Barricade is much like the famous trash-catching wheel installed in Baltimore harbor. It works—so does the very unsexy but useful task of picking up trash on the beach or on the side of the road. But the barriers are a stopgap measure until we deal with our infrastructure and waste reduction problems.