There’s a lot more behind that bedside lamp than just a flip of the switch. Every power button we push relies on electricity that comes from a variety of sources: from burning greenhouse gas-emitting fossil fuels to tapping renewable energy options like solar.

Residential energy use accounts for around 20% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US.1 This just goes to show how electrifying our homes and upping their efficiency can make a huge difference in terms of climate impacts—as well as building a sustainable future for our families and communities. Here’s what you should know about where your electricity comes from.

What energy sources do U.S. homes use most?

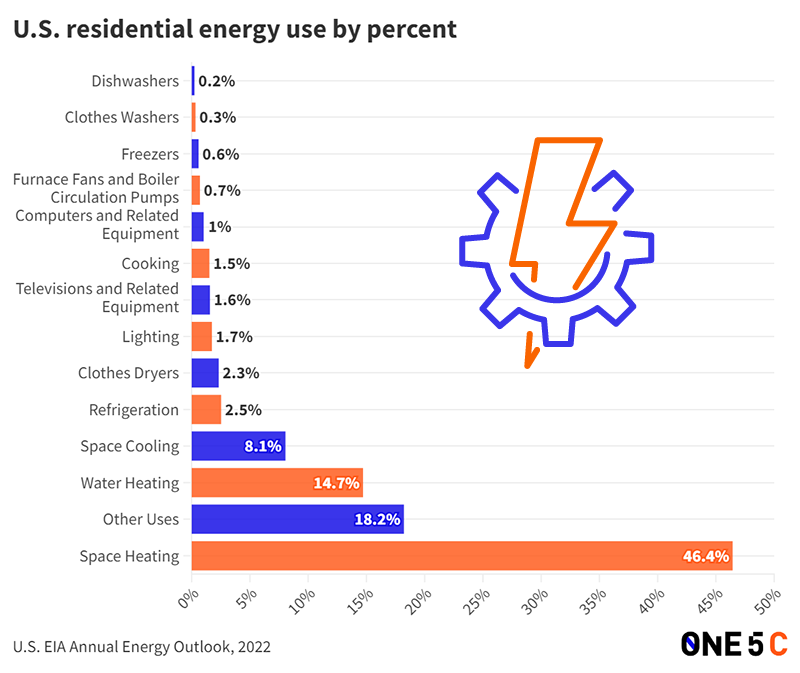

Around three-quarters of homes in the U.S. tap into two or more energy sources, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). In most homes, it’s largely a conversation about electricity and natural gas.2 More than 60% of U.S. residences use natural gas hookups for space and water heating, cooking, and drying clothes, which accounts for 43% of residential energy consumption. There are regional differences in what else a household might tap; for example, more rural homes use propane tanks for heating and cooking, and Northeasterners are more likely to heat their homes with oil, according to the EIA.

What directly consumed fossil fuels don’t take care of falls to either electricity purchased from a utility company (that’s “retail” electricity) or small-scale renewables like rooftop solar panels. According to the EIA, retail electricity accounts for 44% of U.S. residential energy usage. In terms of greenhouse gas emissions, where those electrons come from is what makes the difference.3

What are the main sources of electricity in the U.S.?

Fossil fuels like natural gas and coal account for a majority of the energy that electrifies American homes and workplaces. But according to the EIA, fossil fuels have been making up an increasingly smaller slice of the total since roughly 2008. That year, coal, natural gas, petroleum, “and other” fuels accounted for 2.9 trillion kilowatt hours (kWh), or about 71% of total electricity generation. Renewables and nuclear energy made up the other roughly 29% back then.4 “If you’re in 2005 and said where coal would be in 2024, no one would believe you. Because most people thought coal would just continue to grow,” says Greg Nemet, a professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin Madison.

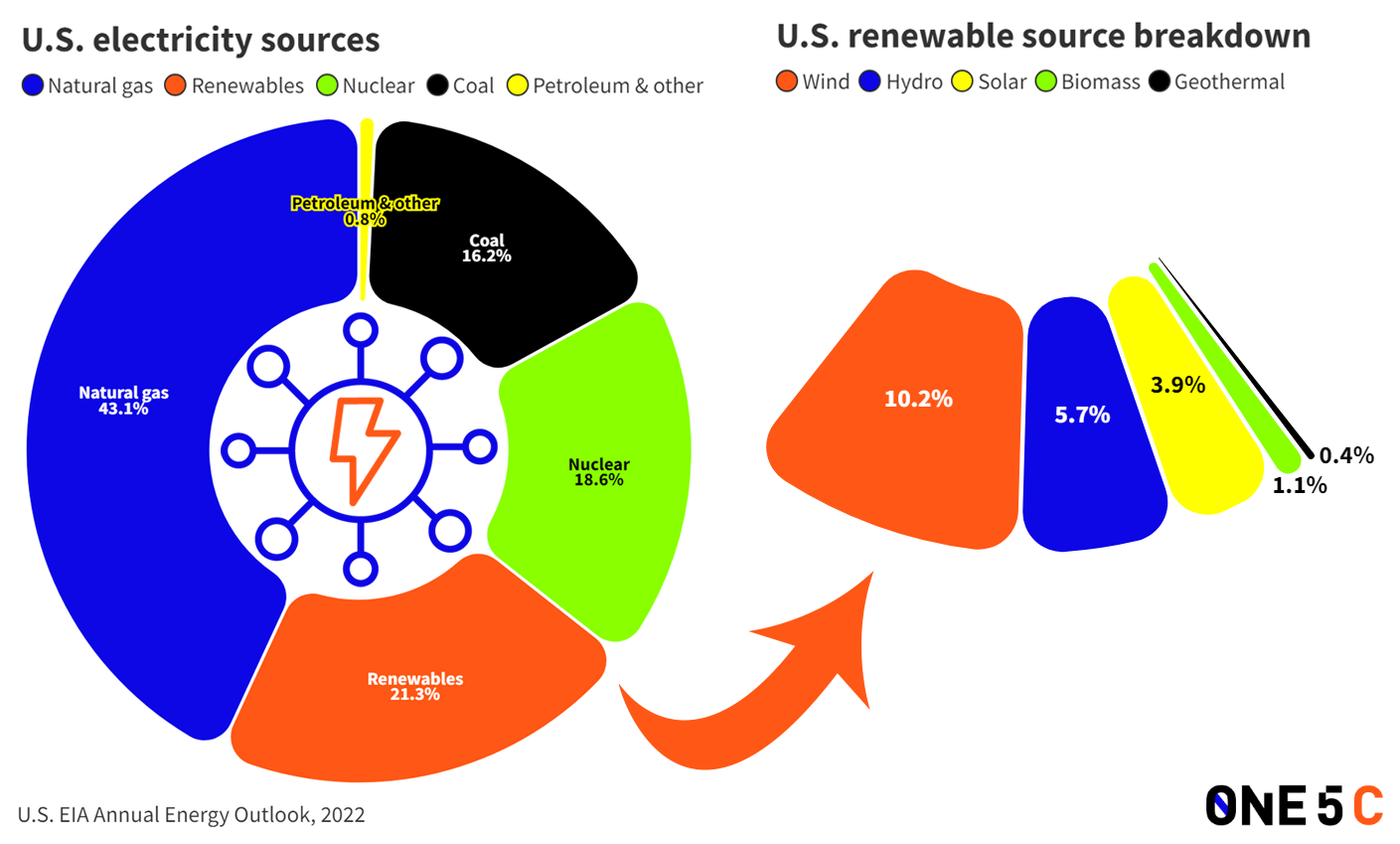

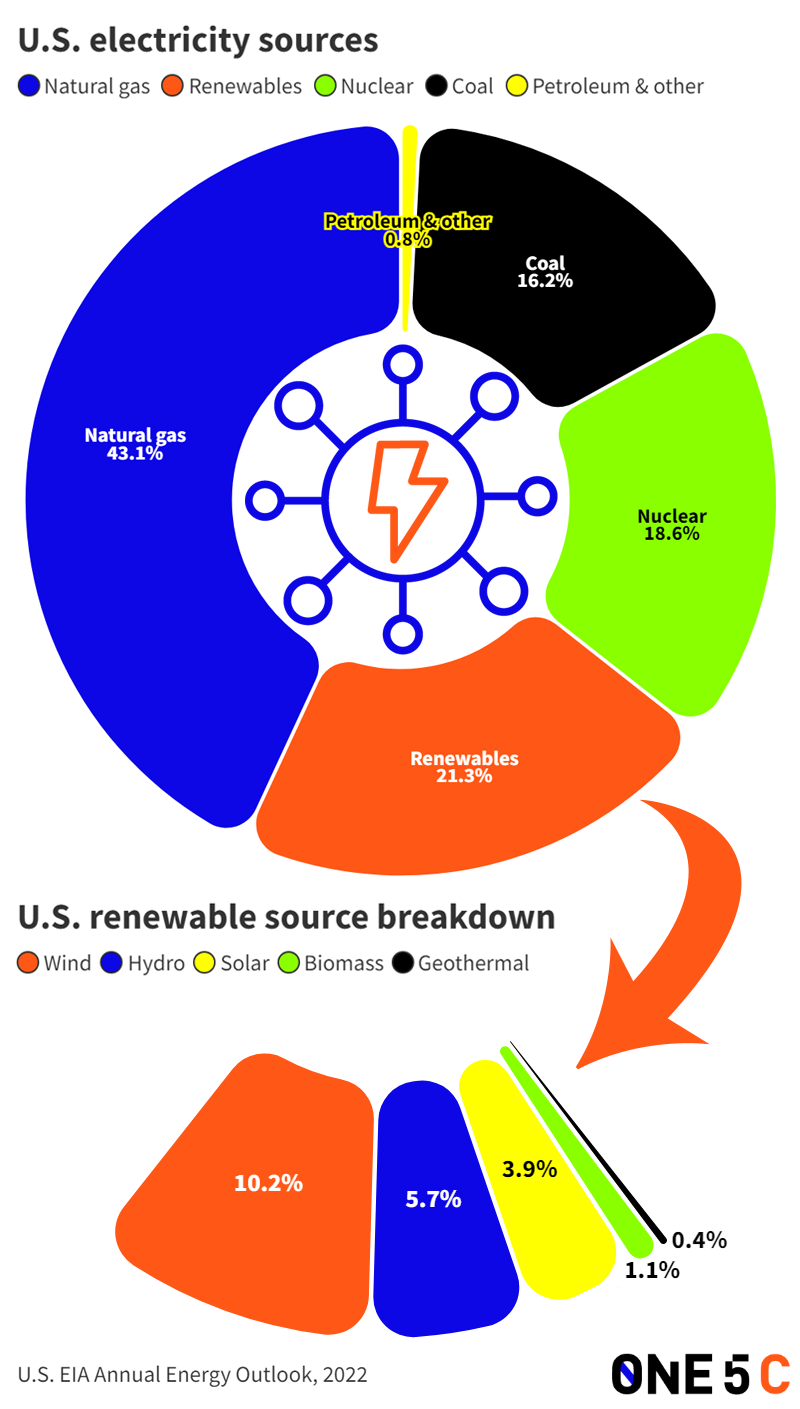

The most recent EIA data has shown fossil fuels’ share drop closer to 60%. In the U.S., natural gas accounts for 43% of the country’s electricity generation). Coal and nuclear energy each accounted for 18% a piece, while renewables have grown to supply 21% of total U.S. electricity generation. Renewables as a whole surpassed coal in electricity generation for the first time in 2022.5

Trends in the U.S. electricity mix are similar to those in the rest of the world, where most electricity comes from fossil fuels, particularly coal and natural gas, with renewable sources edging in on the race. According to the International Energy Agency, combustible fuels generated 65.3% of global gross electricity production in 2019, with the majority coming from coal (36.7%) and natural gas (23.5%). Hydropower has been the world’s main renewable source of electricity, accounting for 16% of total generation, and nuclear makes up a little more than 10%. Renewables overall represented 27% of the global electricity mix in that same time period.6

What makes up the U.S.’s renewable energy mix?

While it’s fantastic news that renewables passed coal in the electricity-generating hierarchy, electricity demand is on the rise. If we want to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, especially as electricity demand is projected to account for over 50% of all energy needs by mid-century, the majority share of fossil fuels in the mix needs to drop below 30% by 2030.7 Department Of Energy officials expect significant increases in solar energy capacity, as well as more wind power to come online by 2025.8

Renewable sources harness the powers of water, wind, the heat of the Earth, and sunlight. There are various ways to gather up the energy from these sources: photovoltaic solar panels utilize the sun’s rays, while turbines use wind to generate energy.

Hydropower is the most prevalent form of electricity-generating renewable energy globally. Hydroelectric facilities (such as dams, which many places in the U.S. are actually abandoning) rely on the force of a waterway to move a turbine and generate electricity.

According to the IEA, hydropower generates more electricity than all other renewables combined, at an estimated 4,300 terawatt hours (TWh) globally in 2022. In the U.S., hydropower has been the historical go-to for renewable energy, but has largely leveled off while other sources have grown steadily since the 1990s and 2000s. In America, hydropower generated an estimated 240 billion kWh of electricity in 2023, making it the second-most prevalent renewable in the country that year and 5.7% of the total electricity mix.9

Wind power currently takes first place for renewable electricity generation in the U.S., accounting for an estimated 435 billion kWh in 2023 (accounting for 10.3% of the total, according to the EIA). This type of technology relies on large wind turbines that generate electricity as gusts move propeller-like blades on a rotor, which spins a generator. In 2023, wind power saw about $12 billion in capital investment in the U.S., leading the DOE to forecast a 60% increase in growth for new land-based wind projects in the coming years.10

Solar power relies on capturing the energy of sunlight. The growth of solar has surpassed wind development in the U.S., accounting for 37.6% of new electricity capacity installed in 2022, according to S&P Global.11 EIA data shows that solar technology provided an estimated 3.9% of total electricity generation in 2023. Worldwide, solar capacity has been growing exponentially, the IEA says, accounting for 1,293 TWh of power generation in 2023—a 515% increase from the 251 TWh produced globally in 2015.

Bioenergy, which includes biomass and biofuels, is a source of power derived from organic materials such as plants. Energy can be harvested from these materials (everything from grass clippings to food waste) by burning them, by bacterial decay, or, in some cases, they can be converted into liquids that can be used as biofuels (like ethanol). While bioenergy is not a leading source of power for electricity needs, it is actually the largest source of renewable energy globally. It’s used mostly as a fuel or fuel additive for vehicles, and is expected to grow particularly in emerging economies like those in India and Brazil, the IEA notes. However, burning biofuels is not the most eco-friendly energy option; while the resources it requires are technically renewable, it still needs to be grown and harvested–not to mention it emits carbon when burned.12 Biofuel waste also creates significant air and water pollution.

Geothermal technologies harness the energy from the heat of the Earth itself. Wells tap into underground reservoirs of hot water to run heating systems, or water flowing among hot rocks deep below the surface can be used to generate steam and drive turbines that generate electricity. In the U.S., geothermal accounted for about 0.4% of the total electricity produced in 2022.

Are renewables more expensive than fossil fuels?

In a word: No. In the last decade or so, prices for renewable energy have plummeted, and electricity from those sources now costs less or is comparable to conventional options like fossil fuels. The costs to build solar in particular have dropped an estimated nearly 90% during that time frame.

The actual price of power all depends on which type of renewable energy is being used and, in some cases, where. Geography plays a big role in the cost of electricity due to the location of natural resources (be it fossil fuels or access to wind and sunlight), labor costs, and regulations.13

The more sources of renewable power that are built, the cheaper that power source can become—particularly as developers of these projects see cost savings from more deployment and better technologies, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). In 2022, the price of electricity provided by onshore wind decreased by 5%, and solar by 3% compared with the year before.14 That’s after onshore wind costs dropped 15% from 2020 to 2021 and solar dropped 13%.15 Around the same time, fossil fuel costs took a big jump.16 The global weighted average cost of electricity from solar, for example, is now about one-third less than the cheapest fossil fuel alternative.

Beyond pocketbook issues, the long-term returns on investment, not just measured in dollars and cents, are almost undeniable for an emissions-free future.

Can I choose where I get my electricity?

That depends on where you live. Many Americans get their power from government-regulated, regional monopolies run by utility companies such as Duke Energy in the Southeast, Exelon in different parts of the country, and Pacific Gas & Electric in California. According to the EPA, only 18 states and Washington D.C. have choices for utility companies available—but even they are often limited.

A lot of utility companies exist in a “regulated wholesale market.” In these instances, electric companies effectively work as vertical monopolies; they generate, transmit, and distribute electricity from start to finish with oversight from state public utility commissions. Most people living in the West and South live in this type of market. In contrast, “deregulated” or “restructured” markets have separate entities generating and distributing power. Organizations called ISOs and RTOs manage the relationship between the two parties. These restructured markets encourage competition, which, in some cases, has led to more providers turning to renewable sources.17

The ability to choose where your electricity comes from—that’s called “retail choice”—is more common in restructured markets, but it’s not a hard-and-fast rule that that will be the case. And remember, in these instances you’re choosing who generates your electricity, as opposed to who sends it to your home.

If you live in Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, or Washington D.C. you have some retail electricity choice. In California, Georgia, Michigan, Oregon, and Virginia there is a more limited type of electricity choice.18 Elsewhere, you have no choice in who provides your home with electricity. This state-by-state guide compiled by the American Coalition of Competitive Energy Suppliers shows the choices available to customers in certain states.

When choosing your provider, check if there are options to source your energy 100% from renewable sources. There are several utilities that offer this: for example Green Mountain Energy in several states, Clean Choice in several states, and Octopus in Texas. Some utility options, such as Arcadia and NRG, will purchase RECs to offset your energy use. Another thing to consider is Green-e certification, which ensures that renewable energy purchases meet certain environmental and consumer protection standards, and provides a helpful database for hunting down wholesale renewable energy providers that may be available in your region.

What can I do if I can’t pick my electricity provider?

Even if you can’t pick your provider, there may be other ways that you can support more renewable energy sources getting thrown into the mix. Along the East Coast, offshore wind projects are moving through local, state, and federal permitting processes that require community feedback. Some businesses (may even your own employer!) might have an opportunity to tap into a community-style approach to power. Or, maybe your house or apartment complex is in the perfect sunny spot for some rooftop solar.

Tap into community renewables

Models are emerging in states and cities across the country that allow customers to tap into shared systems that rely on renewable technology like solar. These decentralized models are most well-known as “community solar” projects, of which there are nearly 3,000 already connected to power grids across the country.19 Though solar is the most popular, these projects, though, aren’t just limited to harnessing the sun: Communities in places like Rhode Island have also installed community wind projects. Twenty-four states along with D.C. and Puerto Rico have laws supporting community solar projects, according to the EPA. Depending on the project, customers can buy, lease, or “subscribe” to a shared power system within a community or business. The renewable generator—i.e., the solar panels and all the gadgets that go along with the tech—could be purchased and owned by the community, a business, or a third party. The Inflation Reduction Act has provided about $7 billion in grant funding that prioritizes residential and community solar projects.

See if rooftop solar is right for you

If your shingles are soaking up that sunlight, why not consider rooftop solar instead? The cost has dropped by more than half, and federal and local incentives can also help offset costs of installation. “Now it’s the cheapest way humans have ever made electricity at scale,” says Gregory Nemet, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the La Follette School of Public Affairs who literally wrote the book on how solar energy became so cheap. Check out our guide to see if rooftop solar could work on your home.

Use less electricity at times of peak demand

Paying attention to “beat the peak” advice can actually make a huge difference in how dirty your electricity really is. At those peak times—afternoon or post-work hours on extremely hot, summer days, for example—avoiding powering up certain appliances (the heavy hitters like washing machines or air conditioning) can relieve pressure on the grid when demand for electricity is highest. Because electricity is mostly generated on an as-need-basis (there’s also a 30% tax credit for energy storage technologies), peak demand not only exponentially drives up the price of each kilowatt hour but also means more power will be produced by power plants that rely on fossil fuels like coal and natural gas.20

- The Carbon Footprint of Household Energy Use in the United States, PNAS, Jul. 2020 ↩︎

- Monthly Energy Review, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Jul. 2024 ↩︎

- Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS), U.S. Energy Information Administration ↩︎

- Monthly Energy Review, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Jul. 2024 ↩︎

- Electric Power Monthly, U.S. Energy Information Administration, May 2024 ↩︎

- Electricity Production, IEA, 2019 ↩︎

- Amplification of Future Energy Demand Growth Due to Climate Change, Nature Communications, Jun. 2019 ↩︎

- Renewable Energy Resource Assessment Information for the United States, U.S. Department of Energy, Mar. 2022 ↩︎

- Electric Power Monthly, U.S. Energy Information Administration, May 2024 ↩︎

- Wind Energy Market Reports, Wind Energy Technologies Office ↩︎

- US Generating Capacity Additions Down YOY in 2022; Solar Takes Top Spot, S&P Global, Jan. 2023 ↩︎

- Bioenergy Production and Environmental Impacts, Geoscience Letters, May 2018 ↩︎

- Midwest Information Office, U.S. Bureau or Labor Statistics, 2024 ↩︎

- Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2022, IRENA, Aug. 2023 ↩︎

- Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021, IRENA, Jul. 2022 ↩︎

- Surging Energy Prices in Europe in the Aftermath of the War: How to Support the Vulnerable and Speed up the Transition Away from Fossil Fuels, International Monetary Fund, Jul. 2022 ↩︎

- An Introduction to Retail Electricity Choice in the United States, 21st Century Power Partnership, Aug. 2017 ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Sharing the Sun: Community Solar Deployment, Subscription Savings, and Energy Burden Reduction, NREL, Jul. 2021 ↩︎

- Electricity: Information on Peak Demand Power Plants, U.S. Government Accountability Office, May 2024 ↩︎