Last week, Coca Cola announced that it was evicting Sprite from the lime-green plastic bottle it has lived in since the 1970s. From now on, those who obey their thirst will grab clear bottles from the cooler. Coke’s reason: The uncolored stuff is easier to recycle. The greenwashing jokes just write themselves, folks.

So yeah, don’t give too much thought to this announcement. It’s another completely defensible Big Company Press Release Moment that is technically slightly better for the environment but doesn’t actually address the real issue. Do not write James Quincey a thank-you note or reassess your commitment to 7UP. (Except let’s be very real here: 7UP is disgusting.)

Yes, it’s easier to recycle plastic that doesn’t have any dyes in it. The House of Lymon can now be ground up, melted down, and turned into a larger variety of soda bottles, synthetic textiles, and other single-use plastic items—to a point. PET can only be recycled one to three times, and it’s an energy-intensive process.

The soda-bottle cycle is a kick-the-can perversion of the circular economy, which, in its most perfect form, allows us to rely solely on the stuff we’ve already dug out of the earth by reprocessing old products into new items. It’s a great goal, and it works pretty well with metal and glass, most of which doesn’t lose its physical properties as it gets ground up, melted, and re-combined. Plastic, on the other hand sucks more and more with every trip through the MRF.

Please forgive me for recycling some words, but I did a pretty good job explaining this the last time we talked about the ol’ chasing arrows:

Every time you do this to a piece of plastic, it gets weaker. The mechanical forces and heat break down the polymer chains in the material. That’s why, unlike many metals, you can’t just keep recycling a plastic item over and over again.

Sprite’s move doesn’t address the larger issue, which is that recycling plastic is an inherently flawed process that keeps us reliant on oil, the most common source of its polymers.

This is the first of plastic’s two biggest problems: Energy companies use the stuff to keep us addicted to petroleum, even as we move away from fossil fuels.

That’s why you hear so much about plant-based plastics. Maybe you’ve come across PLA, which stands for polylactic acid? It’s the most common example of non-petroleum plastic. Its polymers can come from a bunch of sources, including corn, sugarcane, sugar beets, and wheat. There are a lot of legitimate critiques of plant-based plastics, the main one being that if you’re growing something people could eat, you should feed it to them rather than use it to make disposable cutlery. (Some companies are making progress with non-edible crops, but you still have to grow the stuff, and that land could be used for food production.)

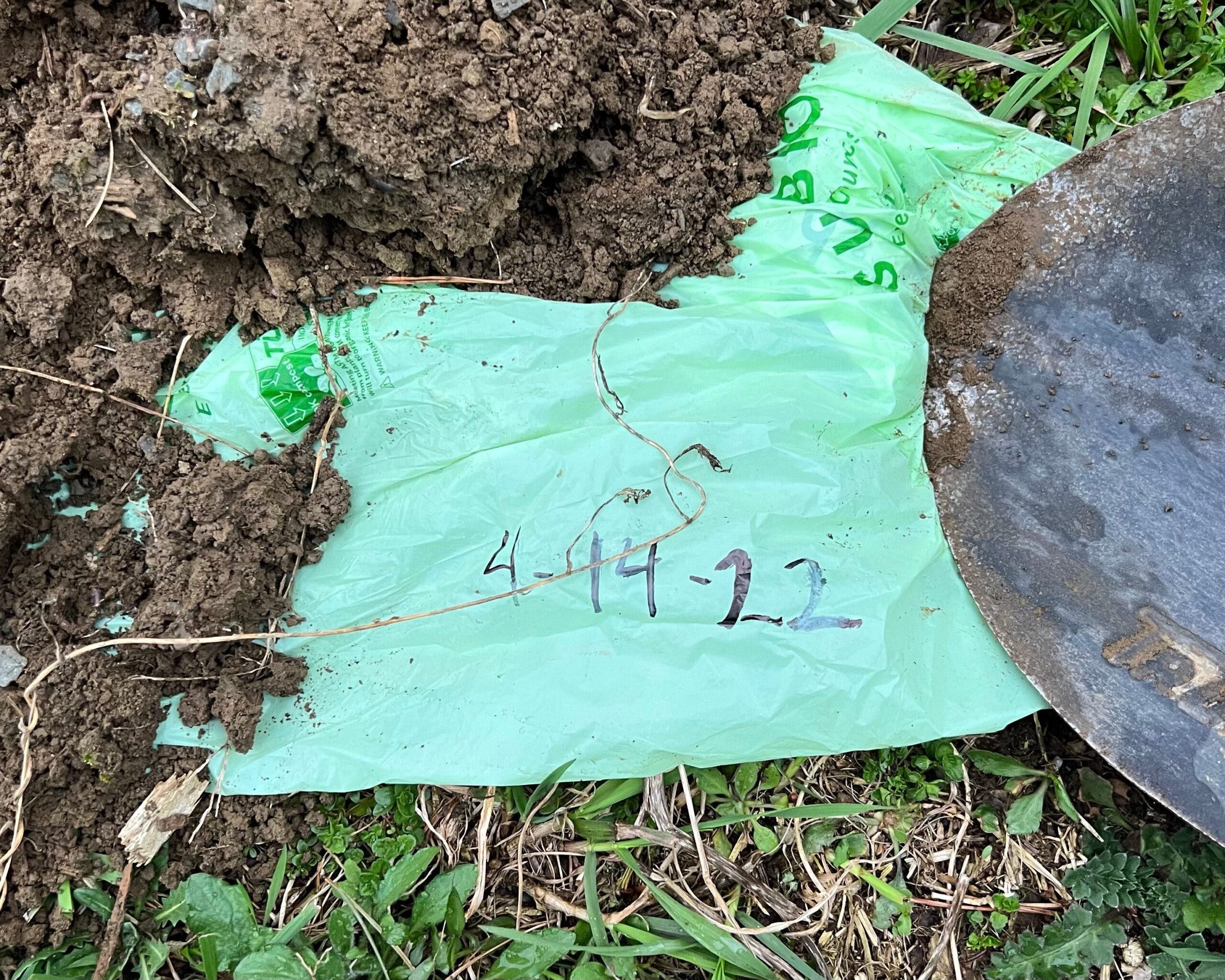

Bioplastics have some other interesting characteristics, like how easy it is to engineer them so they degrade into non-toxic chemicals. Sounds great. If you remember back a few months, we tested out a biodegradable trash bag. Let’s check in on our experiment:

BEFORE – April 14, 2022

AFTER – July 27, 2022

AWESOME GRAPHIC DESIGN TREATMENT – Aug 4, 2022

OK, not great but also not bad, especially considering I just threw a couple inches of dirt over the bag instead of putting it in my actual compost pile. The jerks who owned our home before us left trash all over the property, and I’ve unearthed normal garbage bags that are at least five years old and probably still watertight. According to Superbio, their products will “degrade to humus, CO2, and water within 180 days when placed in a standard compost pile.”

If you dig (hah) a little deeper, though, Superbio and many other compostable plastic products adhere to the ASTM D6400 standard for compostability, which describes the conditions of an industrial composting facility, not a normal yard or even a compost heap. There are products that claim to be “home compostable,” and those mostly adhere to the Australian AS 5810 standard, which is a little different and is aimed at that pile in your (out) back yard

I use some AS 5810-certified cling wrap but I throw it in the trash. I really try not to use it at all, and over the past few months, every time I’ve pulled off a sheet, I’ve thought of the Superbio bag buried by the shed. Why didn’t I put that in the compost pile either?

The answer is that I use our compost in our vegetable garden, and even though every standard for compostable plastic explicitly addresses soil toxicity, I don’t trust it in our produce. Turns out I might be right to be concerned. After I sent out that list of products I bought to replace single-use plastic, an anonymous reader (who are you? I want to say hi!) left a comment: Regarding the trash bags, please reconsider this recommendation.

The reader then dropped a link to a statement by a group called the New Plastics Economy, that cited alarming facts about what are known as oxo-degradable plastics, which are engineered to decompose in the presence of oxygen. The statement cites multiple experts and academic papers, and claims that this stuff, though hailed as a solution, contributes significantly to microplastic pollution.

Remember when I said plastic had two main problems? Microplastics are the second biggie, and there’s a lot of research showing that biodegradable plastics don’t solve the situation:

Studies show that the entire biodegradation process varies, as environmental conditions inevitably do, and often takes longer than has sometimes been claimed. During this time fragments, including microplastics, remain in the environment and the ocean. As with all microplastics in ecosystems, there is a risk of bioaccumulation, including into the food chain, with potential negative impacts on human health and the environment.

The paper went on to discuss other problematic aspects of this type of plastic. A big one is that stuff which is designed to degrade can’t be reused very well, which makes sense. It is flimsy. Another knock is that it can screw with the recycling process, should it get into the mix with our higher-value recyclables. At multiple levels, the stuff undermines the circular economy.

This paper specifically addressed oxo-degradable plastic, which doesn’t have to meet the ASTM D6400 standards, but is marketed in much the same way. I wondered if compostable plastic, home-compostable plastic, and oxo-degradeable plastic all presented the same microplastic risks. So I called Ting Xu, Professor of Materials Science Engineering and Chemistry University of California Berkeley, whose work focuses on the teeny tiny particles.

Xu cleared it up for me. “It’s all going to make microplastics,” she says. OK. Shit.

“You cannot avoid microplastic formation, it’s just a natural thing,” says Xu. Why? It’s a stage that all plastics go through as they degrade, whether that happens in 180 days or 180 years.

“Imagine you want to break down a large piece of paper,” says Xu. “First you rip it up into small pieces; then rip those pieces up even smaller. Keep going. Eventually even those tiny pieces will break down into dust, which is like the paper version of microplastic, and from there they can become molecules again.” Paper has to go through all these stages in order to fully break down. The same thing happens with plastic, says Xu, but getting from microparticle to molecule is much harder than in the case of paper.

“Plastic is semi-crystalline,” says Xu, which means that some of its particles are incredibly tough to bust up; at the same time, other parts of the material degrade more easily, which leads to an uneven decomposition full of itsy-bitsy crystalline clumps.

These miniscule clusters make their way into the ocean because some portion of them escape processing facilities—or slough off of plastic litter or the bag decomposing behind my garden shed—and ride the ground water all the way to the coast. Remember that we’re talking about particles that, on the large side, are less than 5mm. Some microplastics are small enough that they’ve been found in human blood. It is in the rain and air. Nothing stops this stuff.

Xu is working on the problem. Her lab’s research focuses on embedding enzymes in plastic that, when activated by a specific catalyst, start breaking down plastic on the nano scale—which busts the crystalline microplastics apart from the inside out. Right now, this happens mainly in Xu’s lab, but some of her students are working on commercializing the technology.

Let’s hope it happens soon. Until then, what do you do? Avoid single-use plastics whenever possible; and, though it doesn’t solve every problem, I believe that bio-sourced plastic is better than the petroleum-sourced stuff. Because F the oil companies and their record profits. (Oxo-degradable plastic is often made from petroleum, so check your labels.)

You probably won’t be 100-percent successful at avoiding single-use plastic. You will order things online, and they’ll arrive packed in plastic pillows. You will use band-aids. You will buy drinks that come in PET bottles, maybe even Sprite.

But doing your best can make a significant difference here; if we all cut our consumption significantly, it will change the market. Full stop, end of story. After all, if companies like Coke stop selling as many bottled beverages, they will make fewer of them to avoid losing money through spoilage or unsold inventory.

The average American buys 156 plastic bottles a year, each of which weighs around 19 grams. That’s almost 3 kilograms—six and a half pounds—of waste plastic per year, per you. Some portion of this will probably end up in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

I started the year aiming to use zero plastic bottles, and I’ve already missed my goal. I’m somewhere between five and 10. Not perfect, but if I can keep this one stat to 10-percent or less of the national average, I’ll still save around two and a half kilograms of plastic. And I’ll be stoked.

Imagine if a million of us can hit that mark; that’s more than 2,500 metric tons of plastic saved. What if the whole country did? That’s almost a million metric tons, and you don’t even have to stop drinking soda. It comes in cans.

Take care of yourself—and the rest of us, too

Joe

joe@one5c.com