Here’s how it should work: you use something made of plastic, maybe it’s a prescription bottle or the bag your veggie straws came in. Once you’re done with the drugs (or the extruded potato sticks that should also be a controlled substance) you throw the empty container in a blue bin. Then some nice people come and take that stuff and turn it into a spaceship. That’s how it should work. That’s not how it works.

The system is stupid and broken and, yes, you can do something to make it better: Sit your butt down, tap the share👇 doodad so all your friends can play too, and let’s get into it.

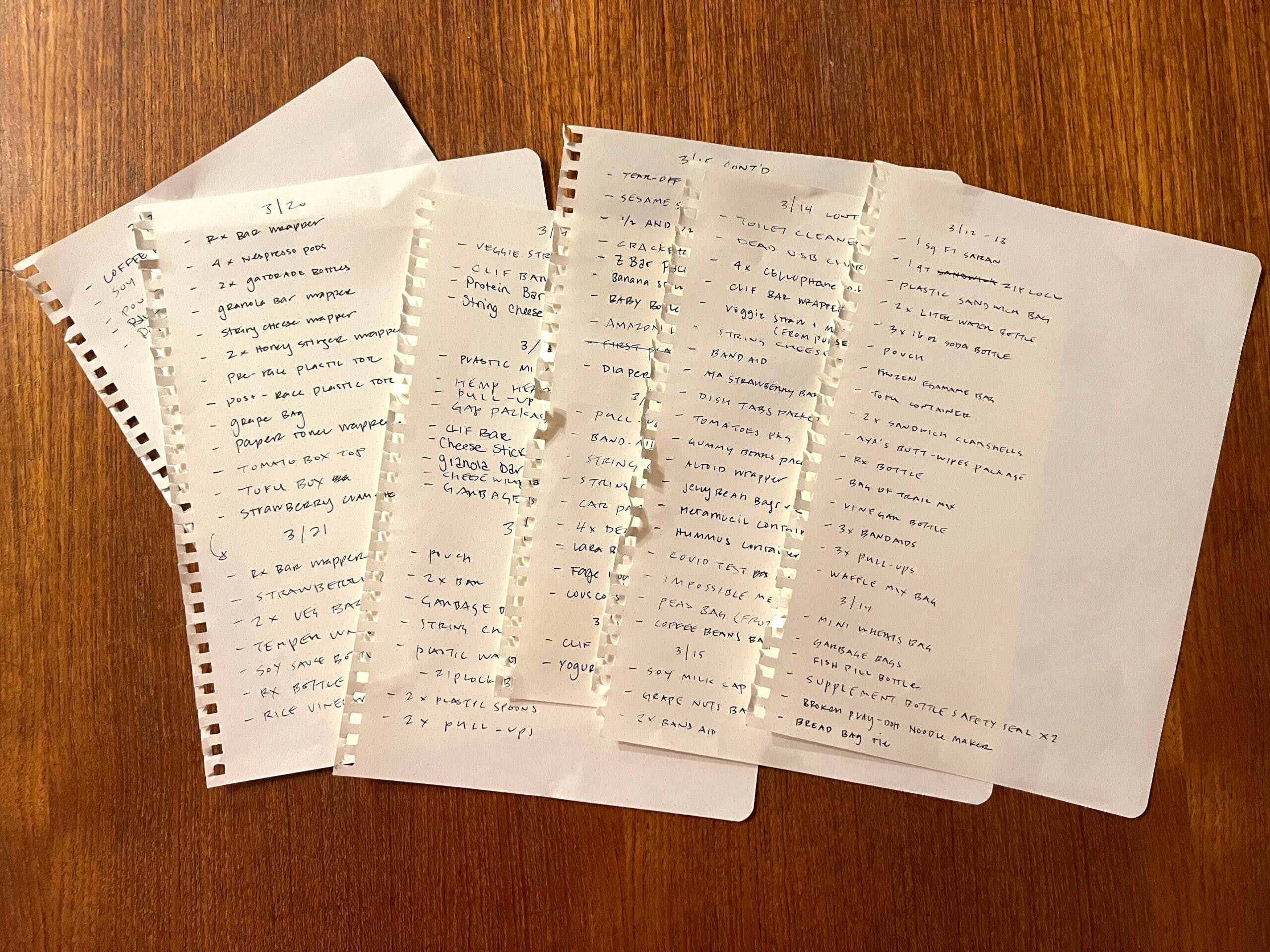

Ready to rock your own world? Make a list of all the plastic you toss in the trash or the recycling bin. Seriously, do it. Maybe you’re awesome and your list isn’t very long. Mine is. My incredibly tolerant wife and I spent a week and a half writing down every bit of plastic that made its way to our curb, and wow. I initially aimed for a month but was too horrified to continue.

Making this list was one of the most eye-opening environmental acts I’ve performed, and I say that as someone who thinks about this stuff all day, every day. Plastic is so pervasive, it manages a sort of invisibility. It is omnipresent, so we tune it out. Your clothes are plastic. Your food is on and in plastic. Your transportation is plastic. Your home: mostly plastic. You are in constant contact with this technology from the moment you open your eyes until the weight of the day snatches your consciousness away. There is so much plastic in our lives, it’s easy to lose track of how much we use once and never think about again.

In 10 days, my family of three logged 138 items. Some of the stuff was abnormal, like the plastic bags full of disposable goodies my wife got for running the NYC Half Marathon (GO CHRISTINE!), but some of it represented essential parts of our daily lives: the pull-up diapers our kid wears to bed, the bandaids, the containers that all our tofu, soy milk, berries, cereal, supplements, snack foods, energy bars, coffee, jelly beans, peanut butter, feminine products, yogurt, and COVID tests come in. (Packaging accounts for 46 percent of all plastic waste.)

Some of the stuff we just shouldn’t use—like the bottles of water we bought at that rest area in Delaware. Or plastic wrap, which I’ve allllllmost quit. Maybe I’m an idiot, but I never thought of bandaids as plastic. I am switching to compostable ones immediately, and I’ll report back when I find a brand that comes close to J&J Flexible Fabric; it’s injury season for the whole family up here in the ag district.

Remember that Richie Havens cotton ad from the 90s? The fabric of our lives? First off, the later Aaron Neville version is better. Second, they’re both false advertising. We’re swaddled in a globe-hugging blanket of plastic.

We put as much stuff as possible in the recycling bin, and probably quite a lot that our carting company doesn’t want. It’s different for every locale, but most facilities are only interested in PET and high-density polyethylene. PET, which also goes by the names PETE and polyethylene terephthalate, is what soda bottles are made of. It wears the mighty number 1, and can make between one and three trips through the recycling process, its final stop usually being some sort of plastic textile. You’ll find high-density polyethylene, or HDPE—number 2—in stuff like cleaning product bottles and the bags inside your cereal box. HDPE has a little more flex than PET and can supposedly be reincarnated up to 10 times.

PET and HDPE are both thermoplastics. For the purpose of a conversation about recycling, you can group plastic into two categories: thermoplastics and thermosets. Thermoplastics live to fight another day, but thermosets only get one trip around the wheel.

“With thermosets, the polymers are all grouped into a solid material, and there’s a secondary reaction called cross-linking that ties them together,” says Scott Phillips, the Materials Science and Engineering professor from Boise State we met last week. “Once you’ve made a shape with that kind of plastic,” he says, “you can’t melt it down and make something new.” Rubber (vulcanized) is a thermoset, as are epoxy and paint. Leo’s famous Bakelite is a thermoset too.

Do you have to keep all this stuff straight? Absolutely not. You’ve probably seen those “chasing arrows” symbols on the bottom of your bottles and jars and in those useless diagrams on websites and trash can lids. I made you a better version, because the other ones suck.

I put a section break in here to create an anchor link. Congrats! You found an easter egg!

You probably know this, but just in case you want a refresher, here’s a very broad description of how recycling works: The contents of your blue bin go to a place called a “materials recovery facility,” more commonly referred to as a MRF. That’s pronounced “Murph,” like the guy your friend brought to that party that one time.

As the plastic travels through the MRF, the people and machines who work there separate what they want from what they don’t. The stuff they don’t want ends up in a landfill or an incinerator or maybe they try to ship it somewhere else. The stuff they do want gets bundled into bales and sold. Then it gets ground into flakes and melted down and molded into another product.

Every time you do this to a piece of plastic, it gets weaker. The mechanical forces and heat break down the polymer chains in the material. That’s why, unlike many metals, you can’t just keep recycling a plastic item over and over again.

Recycling is a physical process, but it’s also an arm of the global materials market. Most outfits that take your junk are doing so because they can process and resell them. A lot of manufacturers use brand-new plastic because, as Phillips says, “virgin plastic is just so cheap.” That particular market force is changing.

Recycling is labor- and energy-intensive, but new plastic’s cost is tied to the price and availability of oil. Oil prices have been on the upswing since last year, driving the price of virgin plastic above recycled in some markets for the first time in years. And now, thanks to Putin’s (🖕) brutal war in Ukraine, they’re headed even higher. According to the plastics-industry analysis firm Chemorbis, prices are going up across multiple subcategories of PET and HDPE. That should be good news for recycling.

This won’t be the case for every plastic, though. Low-density polyethylene, the stuff those crappy grocery bags are made of, carries some famously bad economics, which is why it’s often a no-go for your curbside bin. According to North Carolina’s DEC, it costs about $4,000 to recycle a ton of the stuff. The going rate for a metric ton of ground LDPE, ready to hit the injection molder, is about $750. That’s a math problem even an English major can crack his knuckles over, and the unfortunate answer is a landfill or an incinerator.

If you do a little bit of legwork, though, you can still find a home for it: Some stores take LDPE in the form of clean, used bags and films like plastic wrap. This site lets you search by zip code. If you have some LDPE bags lying around and you’re not going to make a special field trip to get rid of them, just wad them up and shove them in the bottom of your backpack or under the seat of your car. Maybe you’ll use them as an impromptu rain cover, and maybe you’ll have them on hand the next time you notice a place that recycles them. They take up no room at all.

Maybe it shouldn’t be on us to get rid of the plastic that’s been rammed into our lives continuously since the end of WWII, but it is and things could be a lot worse. If you’re grumpy about it, take heart in a new trend: A growing number of states are implementing regulations and even laws based on a concept called extended producer responsibility, or EPR. EPR puts more of the burden on manufacturers to control the waste their products create. In practical terms, that means they have to pay to recycle their own stuff, which means expanded and/or subsidized programs in Your Town. If oil prices keep going up, that’s yet another factor that could make recycling more affordable for communities and private carting outfits.

Whatever the situation, I’m going to keep sorting my trash. My logic is, even if last year’s cereal bags aren’t the stretch in my new undies, the waste companies will have an idea of how much plastic the Browns move through. That data will be important as capacity expands—and I’m confident it will.

Speaking of my family’s plastic, let’s go back to our list: Of the 138 items on it, 65 were recyclable, 59 were no-gos, and 14 were mysteries. I did my best to properly sort the stuff, and likely screwed a lot of it up. There’s probably a person or a robot somewhere cursing my misplaced polymer item as they try to free it from the wheel of their sorting machine, and I would beg their pardon if I could. But they’ll have less plastic from us going forward, because by day two, our list had altered the way we shop and consume.

If you don’t do anything else based on what you read in one5c, make your own plastic hit list this week. I promise you that it will re-wire your brain. Here’s a preview of what you’ll find on the other side: You’re imperfect like the rest of us, but there is a not-insignificant amount of plastic you can cut from your life without really giving up anything at all. You, one person, can keep literal tons of waste from ever being made just by changing some easy habits.

That’s all I’ve got this week. Next Friday, you won’t see me at all—I’m taking some time off. I look forward to seeing you in April.

Take care of yourselves—and each other

Joe

joe@one5c.com