If you look at the numbers, it’s clear that sustainability is, more than ever, not a niche topic. And global warming is a mainstream cultural fact, accepted even by those who roll up to the FEMA tent in a coal-rolling pickup.

But that broad cultural acceptance means that, more than ever, companies and people use the appearance of sustainability to try and sell you stuff. Greenwashing: when someone tries to portray themselves, their actions, and/or their products as better for the environment than they actually are.

No surprise, fossil fuel companies are big into this. They know (and have known) that their products do irreparable harm to the planet; but no oil exec is going to give Don Draper a slow-clap for a slogan like our business is screwing your planet. Instead, they portray themselves as goodhearted, indispensable entities. Just some honest folks burdened by an existing energy monoculture they are obliged to support in order to avoid economic and social collapse. (Not an exaggeration.)

Snort. Don’t buy this line; the drum of change beats fast.

Meanwhile, ExxonMobil recently abandoned its efforts to create algae-sourced biofuels. Sounds cool, but it wasn’t. The program allowed the company to paint itself as a sustainability innovator while continuing to reap massive profits from fossil fuel expansion. It was widely panned as an epic greenwashing campaign.

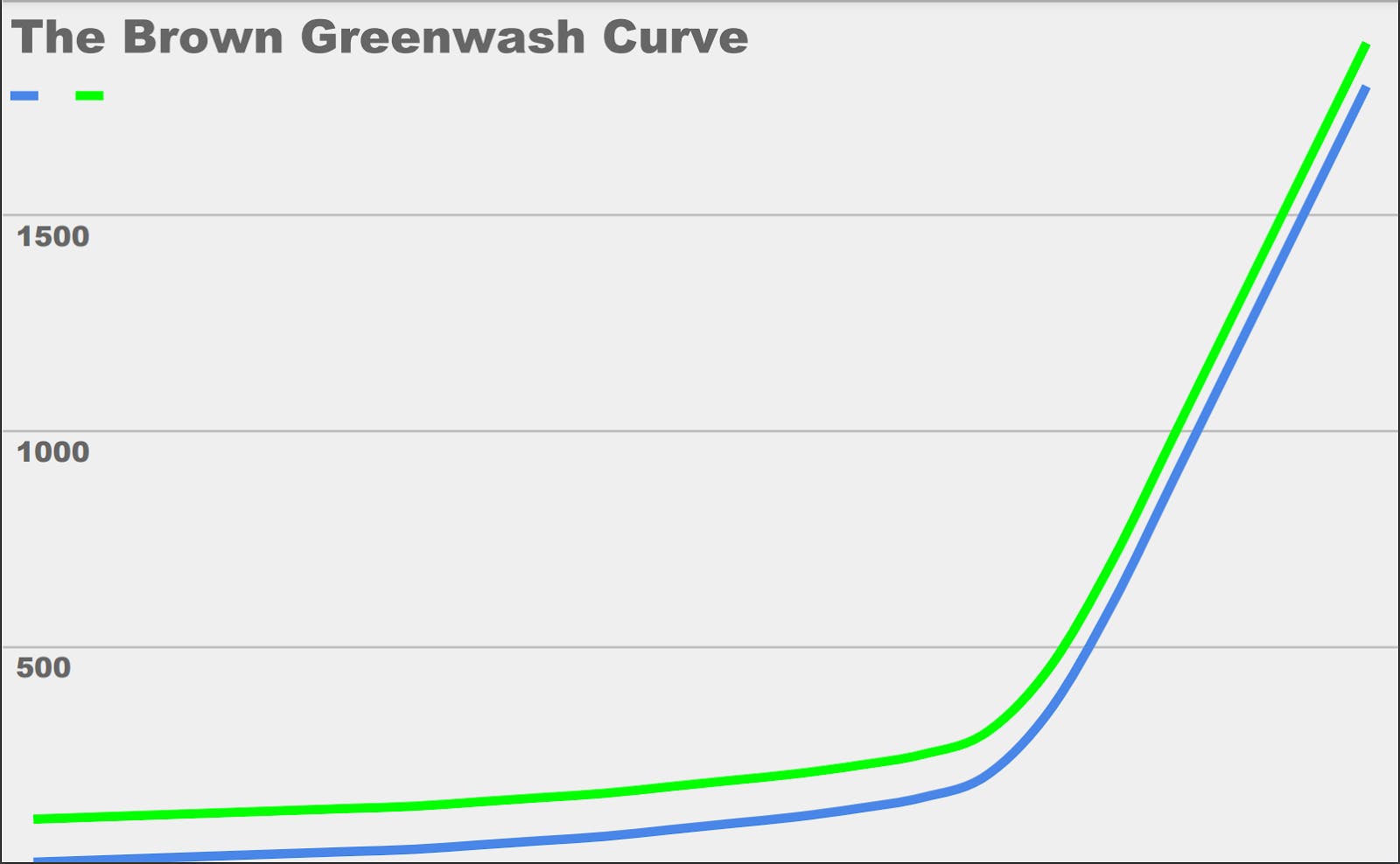

Fossil fuel companies aren’t the only ones to look out for, though: banks, elected officials, even the companies that make the seemingly innocuous trappings of our everyday lives spew greenwash to direct attention away from harm they’re doing. The greenwash usually occurs in direct proportion to that harm. This is a mathematical certainty I’ll call the Brown Greenwash Curve.

Here is a graph:

Some of this stuff is dead-easy to spot, like the phrases “clean coal” (no such thing) and “natural gas” (basically methane). Some is trickier, though, like the cute little “recycle me!” tagline stamped on the bottom of the coffee pod that just popped out of your office caffeine machine.

The coffee is lying to you! Quick, tell your friends.

Yes, you can technically dump out the grounds, scrape off the foil, and deposit a sparkly clean polypropylene pod in your blue bin. Unfortunately, your local recycler probably won’t take that number 5 plastic, and that pod will end up in a landfill. (Stick with drip; both grounds and filters are compostable.) That sustainable stamp really only serves to make a serving of single-use plastic look less harmful than it is.

Maybe this seems like an honest mistake, like the coffee company was duped by the same conspiracy as the rest of us. Doesn’t matter. It’s still greenwash. “Inadvertent greenwash happens a lot now,” says Benjamin Franta, Head of the Climate Litigation Lab and Senior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford Sustainable Law Program. “The people who create the messaging may not fully understand that they’re doing something misleading.” That means you need to be extra aware.

Developing a sense for greenwash is a little bit like honing your street-smarts. The first step is knowing you need to pay attention; and that might be the most powerful action you can take. Even having read this far, you’ll start questioning more statements about sustainability and environmental impact. 💪 But with a little effort and a few tricks, you can get very good at spying even the most subtly misleading statements.

Micro truths can mask macro lies

A claim about sustainability can be technically true while also being an accessory to greenwash. This sounds complicated, but it involves a pattern that’s easy to recognize once you know the signs. “When you see a fossil fuel company say something is ‘lower carbon,’ you have to ask yourself: compared to what?” says Franta. “What they often mean is lower carbon compared to coal.” That doesn’t mean it’s low carbon, just better than the literal highest-emissions crap on Earth.

“These narrowly true formulations are micro truths, and they hide macro lies,” says Franta. A trick for identifying these micro truths is to look for the comparative forms of adjectives—words that end in -er—that aren’t followed by an object of comparison. If the comparison is not specific, “that sets off my greenwashing spidey sense,” he says.

Watch the stars

Oftentimes you’ll see a description of a product or service wearing some jewelry. “Look out for the asterisk,” says Chrsitine Whelan, clinical professor of Consumer Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. That little adornment means that that whatever preceded it needs further explanation.

“There are consumer protection rules about what a company can and cannot say,” says Whelan, “and there may be more to this statement than just what the slogan implies.” The asterisk might take you to a footnote that says something like, these claims have not been evaluated by such-and-such agency; other times it might point you at some research that backs up the product’s claims. “Definitely check out the data,” she says, “because the study they’re quoting could be misleading.”

It’s crummy, but a lot of research is funded by companies or special interest groups whose products they prove to be safe, beneficial, or, in this case, sustainable. This is a huge red flag and it’s easy to spot; studies usually list their underwriters within the first few pages. To be fair, this doesn’t necessarily signal a bunk paper, but “that should make you very suspicious,” says Franta. “Companies don’t usually fund research that hurts their bottom line.”

Beware the proprietary term

Let’s say you’re online shopping, choosing between two water bottles. One of them is made from 100-percent post-consumer, recycled material. The other is crafted of 100-percent Green Econium™️. Which do you go with? Depends on what Green Econium is—and it could be literally anything, because that’s a made-up word.

“This is called reification,” says Franta, “and it’s making something more real than it actually is.” Proprietary terms like this should set off your alarms, because proprietary terms are marketing; and marketing’s goal is to give you a favorable opinion of a company’s goods or services. This doesn’t mean that Green Econium isn’t a fantastic material, but it does mean you should take 3 minutes and try to find out what that stuff actually is.

Read up

Your best defense against greenwash is being informed. “Stay up on the journalism,” says Franta, “because there are some things that you can’t tell from clues in the language the companies use.” That means, of course, continuing to read one5c, but also adding some more sources to your list.

Local news organizations are great resources, because they’ll have reporting on stories that literally hit you where you live. But the national stuff can keep you up to speed on the big issues that are usually addressed in the most sophisticated greenwashing campaigns.

Here’s some of stuff I read:

Grist, a nonprofit news organization with a focus on climate justice. I know a few folks who work there, and they are some of the journalists I admire most. In a world where we expect to receive news in our inboxes and social channels, I type g-r-i-s-t-dot-o-r-g into my browser every day.

Inside Climate News ICN describes itself as “Pulitzer Prize-winning, nonpartisan reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet,” I can’t write a better description than that. In particular, I like their newsletters. “Today’s Climate” comes out twice a week, and “Inside Clean Energy,” is a weekly that focuses on the energy transition. You can subscribe to them here.

Semafor Net Zero Media startup Semafor’s climate-focused newsletter got off to a real rough start, alienating its launch columnist by serving up greenwash on behalf of fossil fuel companies. Yikes! It was a disaster. I kept my subscription to see how they could possibly recover, and I’m glad I did. Their new climate reporter is doing an excellent job, and I look forward to it every week. It’s very business and international policy-focused. If that’s your thing, I highly recommend it. (And I haven’t seen a misleading ad since the incident.)

The Crucial Years is a legendary environmental journalist, and you can rely on him for keen takes on the biggest issues in climate. I found out about the Inflation Reduction Act from his newsletter. He sent it out at like 10PM the day the legislation was introduced.

MIT Technology Review Full disclosure: Tech Review’s new editor-in-chief is a close friend, and I started reading mostly so I could give him shit and text him about stories he missed. But then I couldn’t stop reading it. Tech Review’s terrific Climate Change topic page functions like a mini publication in and of itself. It’s all well-written, and full of explainers and news you don’t see anywhere else. Foiled again!

I read a lot of other stuff, too, as you might imagine, but this is the essential list.

—

So those are my best tips for spotting greenwash. Now that you know how to catch it, what can you do? First and foremost, if a company is lying to you, don’t give them any money. But you might also have legal recourse.

“States have consumer protection laws,” says Franta. “Often they prohibit not just saying something that is false, but saying something that is narrowly true and misleading.” New York is one of them, and a marketing student here recently sued H&M over claims that it made about its garments’ sustainability.

Maybe lawsuits are the only language big companies understand. Or maybe a couple high-profile cases and increased public awareness will be enough to get them to stop.

Ehhhh, we’ll probably have to sue. Greewashers: Y’all are on notice.

Take care of yourself—and the rest of us, too

Joe

joe@one5c.com