When you think about sustainability in the greater sense, a few visuals may immediately pop into your mind: trees, solar panels, and the iconic recycling symbol. Recycling is an attractive notion, mainly because it doesn’t challenge the way we use plastics in our everyday lives. After all, what’s the harm in using a disposable water bottle if we can just turn it into another one? But, plastic recycling isn’t nearly that simple: It takes resources to break down and rebuild the material, not all plastics are actually recyclable, and those that are won’t necessarily meet that fate.

Recycling is one of the original greenwashing tricks. Globally, we produce 430 million metric tons of plastic every single year, around two-thirds of which is for limited or single-use.1 But our recycling rates are abysmal: The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) puts global recycling rates at about 9%. Another 19% is incinerated, 50% ends up in landfill, and 22% slides into uncontrolled dumpsites, is burned in the open, or finds its way to land and marine ecosystems. Even that number is high compared to rates in the U.S., which according to multiple reports, has slipped down to around 5%.23

The history of plastic recycling

Recycling first picked up steam in the 1970s as plastic became ubiquitous in our lives. The first recycling mill was built in Pennsylvania in 1972, the first curbside recycling program popped up in Missouri in 1974, and, in 1981, Woodbury, New Jersey, became the first city in the U.S. to mandate recycling.

But, spoiler alert, the plastic industry even knew then that recycling was a bunch of baloney. According to reporting from NPR and PBS Frontline, reports dating back to the early 1970s point out that recycling would be costly, that degrading plastics would become harder and harder to reclaim, and that sorting plastics to begin with would be likely “infeasible.”

As people started getting more bothered by the mounds of trash piling up, the petroleum-fueled plastics industry needed a facelift if they wanted to keep selling their wares. Enter highly publicized recycling programs and a $50 million-a-year marketing campaign to get folks to recycle—all funded by oil and chemical companies. Lobbying efforts began across 40 states in 1989 to put the recycling symbol on all plastic, even when no facility could possibly recycle it all. And, from the producers’ perspectives, recycling has never made financial sense. Making new plastics with virgin materials is more affordable, and the world is still en route to tripling our current use by the middle of this century.

GO DEEPER ON THE ROOTS OF PLASTICS RECYCLING:

- Why is plastic bad for the environment

- How much oil goes into making plastic?

- Plastic pollution, by country

- Plastic pollution in in the ocean

How does plastic recycling work?

Around 59.5% of the U.S. population can access curbside or drop off recycling programs,4 but what happens after we toss stuff into the bins? Well, there’s two primary ways of recycling: mechanical and chemical.

Mechanical recycling is by far the most common type currently available. The process goes like this: Machines sort, wash, shred and resize the plastic. Smaller shreds or chunks of plastic are re-identified based on density and thickness, sometimes using water to float the pieces or even wind tunnels. Afterwards, a device called an extruder “compounds” the plastic, which basically means it melts and cuts the plastic into teeny tiny pellets, which can then be used to make fresh plastic.

Chemical recycling is a newer, and rarer process. As of 2022, the U.S. only had eight chemical recycling facilities countrywide. This endeavor utilizes chemicals or extreme heat to turn plastic back into its original building blocks, or monomers, which can then be used to make a variety of things—from more plastic to fuel. Chemical recycling, while seemingly pretty awesome in its ability to completely revamp plastics, has some nasty environmental side effects: hazardous waste, resource use, and a much-higher greenhouse gas footprint than its mechanical counterparts.

GO DEEPER ABOUT THE PLASTIC RECYCLING PROCESS

The benefits and downsides of recycling plastic

Recycling, in theory, could be incredibly beneficial to the planet and local economies. Slowing down the rate of plastic entering natural ecosystems can theoretically lower clean-up costs, and recycling plastic can make more room in existing landfills, holding off the expensive process of waste disposal.

But, the dark sides of recycling are numerous. Facilities have been found to wash microplastics off into waterways.5 Mechanical recycling releases chemicals like benzene, increasing the toxicity of second-life recycled products.6 The most obvious problem with recycling, however, is downcycling. Plastics can’t be recycled forever, and even the most recyclable products only make it one or two times through the process. It’s also really easy to contaminate a batch of recyclable plastics with non-recyclable items or bioplastics. Not to mention, in today’s economy it is cheaper for companies to start new with virgin, fossil materials than to make use of recycled plastic.7

GO DEEPER ABOUT THE GOOD, BAD, AND UGLY OF RECYCLING

- Benefits of plastic recycling

- Problems with plastic recycling

- How many times can plastic be recycled

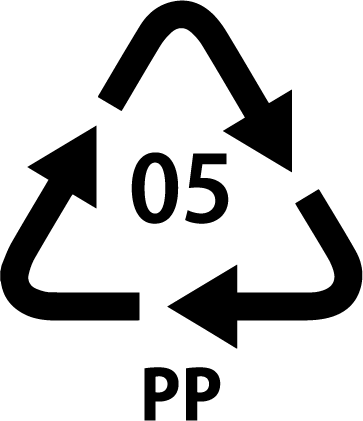

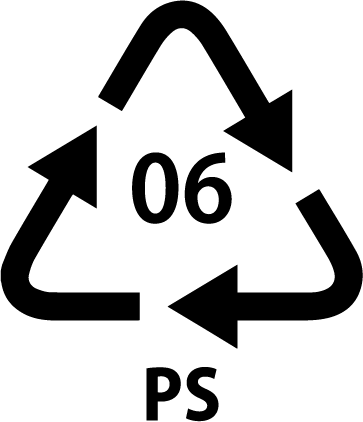

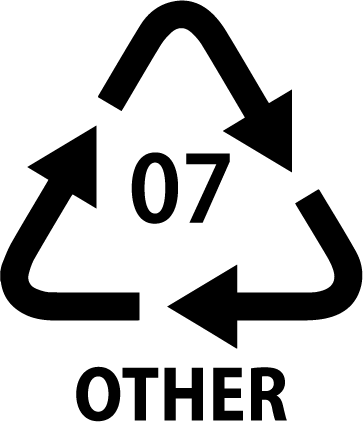

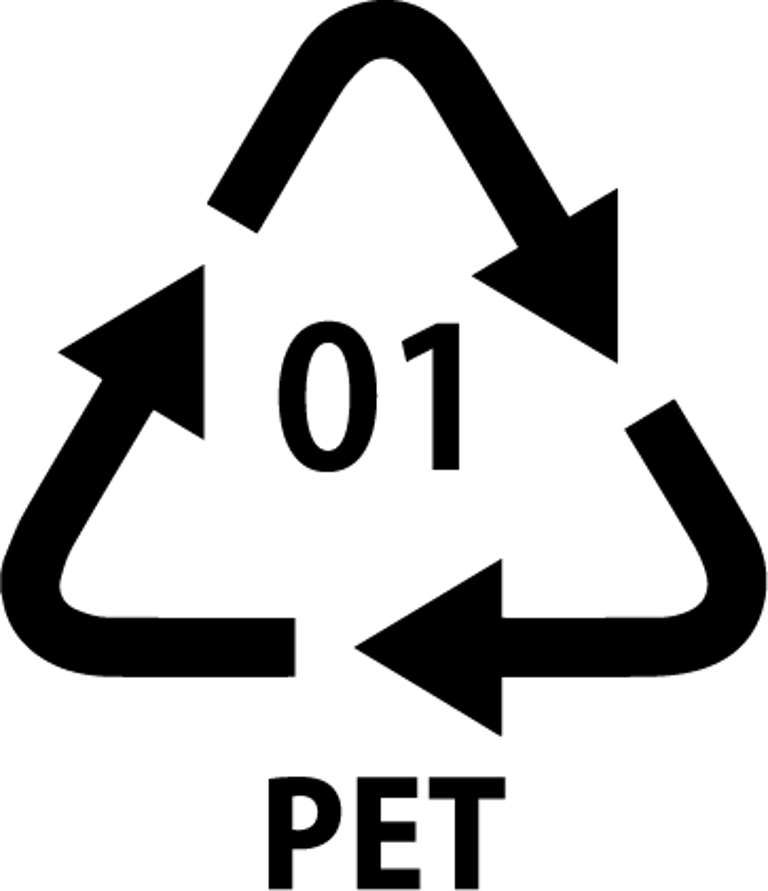

What do recycling numbers mean?

What we think of as “plastic recycling numbers” are actually resin identification codes. These little symbols found on all sorts of plastics were created by the Plastics Industry Association in 1988 to identify the type of material at hand. The symbols, however, have confused consumers on what should and shouldn’t end up in the recycling bin ever since. Here’s a breakdown of what the seven plastic numbers mean:

| Types of Household Plastic | |||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Plastic type | PET | HDP | PVC | LDPE | PP | Poly-styrene | The misfits |

| Common products | Bottles, food jars, condiment and dressing bottles | Cleaning supply bottles, milk jugs, shampoo bottles | Pipes, cables, medical devices, Toys | Shopping bags, bread bags, plastic wrap | Straws, bottle caps, yogurt containers | Packing material, takeout containers, coffee cups | Baby bottles, automotive parts, food containers |

| Accepted at standard facilities | Yes | Yes | Rarely | Rarely | Rarely, but getting more common | No | No |

| Plastic type | Common products | Accepted at standard facilities |

| Bottles, food jars, condiment and dressing bottles | Yes |

| Cleaning supply bottles, milk jugs, shampoo bottles | Yes |

| Pipes, cables, medical devices, Toys | Rarely |

| Shopping bags, bread bags, plastic wrap | Rarely |

| Straws, bottle caps, yogurt containers | Rarely, but getting more common |

| Packing material, takeout containers, coffee cups | No |

| Baby bottles, automotive parts, food containers | No |

PET, or what makes up single-use drink bottles, is one of the most recycled types of plastic in the U.S. with a rate of around 28%.8 But other types of plastic, like the stuff that makes up plastic film and throwaway grocery bags called LDPE, is much more complicated.

GO DEEPER ABOUT RECYCLING DIFFERENT PLASTICS

- Recycling numbers and symbols, explained

- Can you recycle plastic bottles?

- Can you recycle plastic bags?

Can the plastic crisis be solved?

Solving the plastic pollution crisis requires many things. First, we need to reduce the amount of plastic created. Period. Then we need to ensure that the plastic we do use ends up recycled—or at least not in the environment. In other words, we’ll need to dramatically change the way we look at single-use plastics and the recycling system as a whole. This will involve international cooperation (something happening at a rate that experts say is much too slow),9 local legislation like plastic bag bans, holding businesses accountable for their own waste, and individual action. On the big scale, voting, protesting, and donating money can help. But addressing the plastics crisis also means addressing our day-to-day reliance on plastic by saying goodbye to single-use products as much as we can.

GO DEEPER ABOUT PLASTIC RECYCLING SOLUTIONS:

- Global plastics outlook: Policy scenarios to 2060, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Mar. 2022. ↩︎

- The real truth about the U.S. plastics recycling rate, Beyond Plastics, May 2022. ↩︎

- Circular claims fall flat again, Greenpeace, Oct. 2022. ↩︎

- Centralized Study on Availability of Recycling, Sustainable Packaging Coalition, Jul. 2021. ↩︎

- The potential for a plastic recycling facility to release microplastic pollution and possible filtration remediation effectiveness, Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, May 2023. ↩︎

- Forever toxic: The science on health threats from plastic recycling, Greenpeace, May 2023. ↩︎

- Quantification and evaluation of plastic waste in the United States, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Aug. 2022. ↩︎

- 2021 PET Recycling Report, National Association for PET Container Resources, Dec. 2022. ↩︎

- Progress on plastic pollution treaty too slow, scientists say, Nature, Nov. 2023. ↩︎