Despite how much your parents may have flipped out on you as a kid, leaving a light on in another room isn’t what’s going to rack up a giant electricity bill. (Thanks, LEDs!) Sure, tiny actions draw valuable juice and do add up, but there are other, much bigger, players feeding in a home’s power drain.

Climate control has been—and will continue to be—the biggest energy hog in most American homes. Appliances that handle heating and cooling (which includes water heating) accounts for more than 40% of the electricity consumed by residential users, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).1 Much of that electricity still relies on burning fossil fuels. On top of that, home electricity demand has drastically changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shifted many people to remote and digital-focused working conditions.2

It’s important to remember, as well, that energy and electricity are not synonymous. Electricity is an “energy carrier,” which is to say that electricity is a form of energy that enters your home—the same way spaghetti is a form of pasta that enters your mouth. Electricity can be generated by a variety of energy sources, including renewables like wind and solar and fossil fuels like natural gas and oil.

According to the EPA, residential electricity accounted for 9.1% of the U.S.’s total emissions in 2021, with about 578.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emitted that year.3 That’s about as much as running 1,500 power plants for a year. For those hoping to slim down their home’s demands, understanding the biggest energy sucks is crucial—and we’ve got the low down right here.

How much electricity does the typical household use?

According to EIA estimates, the average American household uses about 10,791 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity annually, or about 899 kWh per month. That’s about 29.6 kWh per household per day, to power everything from climate control equipment and appliances to lights and gadgets.4 In terms of potential planet-warming emissions, that puts a home’s electricity draw at about the same level as driving a gas-powered car for a year.5

There are, of course, regional differences in a home’s demand. The highest household draw in 2022 was reported in Louisiana (14,774 kWh a year), and the lowest was in Hawaii (6,178 kWh a year). That draw can mean vastly different things for the climate based on location and the grid. In Hawaii, for example, solar provided 19% of the state’s electricity, whereas Louisiana is far more reliant on fossil fuels.6,7

What areas of a home use the most electricity?

Even though modern-day appliances are far more energy-efficient than their predecessors, analysis published in the journal Applied Energy has found that domestic appliances have actually been demanding more energy year-over-year.8 In fact, the amount of electricity consumed in the U.S. in 2022 was 14 times greater than the amount used in 1950, according to the EIA. That year, which is the most recent year for data from the agency, set a record for the amount of electricity used at about 4.07 trillion kWh.9

In our households, rising demand comes from a combination of appliances such as space heaters, refrigerators, and televisions.

Climate control & water heating

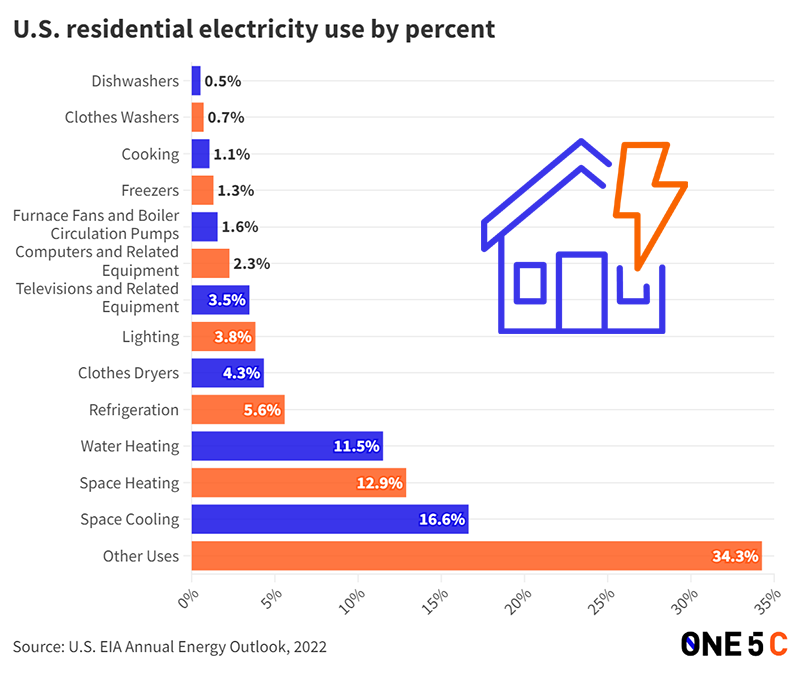

Heating and cooling account for 41% of the total electricity used in U.S. homes according to EIA data, making HVAC the largest piece of each home’s demand. Space cooling, in particular, accounts for the largest electricity draw in American homes at 16.6%. Space heating accounts for 12.89%, and water heating accounts for another 11.5%.

Refrigeration

Fridges and freezers represent the next-largest category of home energy hogs. Keeping food and beverages chilled to the proper temperatures make up about 7% of a household’s electricity demand according to EIA’s data.

Clothes washers and dryers

Taken together a household’s laundry routine can account for more than 5% of the electricity it uses—though it’s important to remember that that number doesn’t account for the energy used to heat up water for warm wash cycles. Dryers, in particular, are major electricity hogs at 4.3% of the home’s draw.

Lighting

Though the end of the incandescent bulb and the rise of the LED has spurred steady declines in lighting-related electricity draw, keeping a home well-lit still accounts for 3.8% of a household’s average draw.

Electronics

TVs and the equipment that goes with them—think consoles and cable boxes—sip around 3.5% of a household’s electrons. Similarly, computers and their various peripherals make up about 2.3% of a home’s total draw.

Are there energy-efficient alternatives to high-wattage appliances?

In many cases, yes—and there could be even more soon. As the Department of Energy codifies new energy-efficiency standards for appliances like clothes washers and dryers, those already on the market promise to save consumers hundreds, if not thousands of dollars on their energy costs. Appliances that include an Energy Star seal typically exceed federal minimums for efficiency. At the same time, those bright yellow EnergyGuide labels should provide information about the device’s energy needs and how it compares to similar appliances.

How to estimate your home’s electricity use

When it comes to figuring out how much electricity your home in particular is demanding, your monthly electricity bill is a good place to start. If you don’t have any bills to look at, or are trying to budget for a new home or for someone else, the Department of Energy recommends doing some math.

A simple formula for daily energy consumption is to multiply the wattage of an appliance and the hours it is used per day, then divide that number by 1,000 to calculate daily kWh consumption per appliance. Once you figure that out, multiply that by the number of days that appliance is used throughout the year.

For example, a $175 window air conditioner available today runs about 455 watts. If that unit runs for 24 hours a day, its daily energy consumption would be about 11 kWh. If it runs every day for four months out of the year, that AC unit would suck up 1,320 kWh annually, which would account for roughly 12% of the average U.S. household’s annual electricity needs.

Repeat this process across the home’s major appliances electricity draws, and you’ve got a rough total. If you want to take things a step further, look into getting a home energy audit to check for any weak spots–or places you can make improvements.

How to monitor electricity use

Are smart appliances, monitoring systems, or fancy apps really worth the effort (and price tag)? For those who really want to get a handle on usage and possible inefficiencies without manually tracking gadget-by-gadget, there are a couple options.

Smart meters

The DOE says there are millions of smart meters in the U.S. These devices can provide real-time data on electricity use, and some can even remotely adjust thermostats or appliances. Some utility providers, such as New York State’s NYSEG, offer online tools to connect customers to their data and personalized suggestions on how to reduce the amount of energy they’re consuming at home.

Home energy monitors

Home energy monitors are devices installed in your home’s electrical panel that can provide real-time data on how you’re using electricity. This information can be accessed on the web or with an app). These apps can show where in the home energy is being used and even send users customized alerts for their electricity weaknesses–be it keeping the fan on when nobody’s home or allowing vampire devices to suck up electricity when not in use. Home energy monitor company Sense estimates that their average user saves around 9% on electric bills. These monitors can run you up a few hundred dollars, so if that’s out of reach then smart thermostats and programmable light bulbs could be a more cost-effective way to start.

Simple ways to cut electricity use

While major updates like switching your HVAC system to an efficient heat pump or investing in an insulation overhaul and air sealing can greatly slash your home’s electricity draw, there are plenty of day-to-day things anyone can do to limit the amount of juice they use on the regular.

How to up the efficiency of your laundry routine

Revamping the way you clean your duds can add up to huge energy savings. Washing clothes in cold water, for instance, can cut a machine’s draw by 30%. Skipping the dryer altogether also adds up to major savings gains. Here’s our best advice for upping the efficiency of your laundry routine.

How to stay cool (or warm) without blasting the HVAC

In the heat of summer—or the dead of winter—there are simple things homeowners can do to avoid adjusting the thermostat too aggressively. In the steamy months, for example, optimizing your home for ideal airflow can make you feel several degrees cooler. In the winter, you’d also be surprised how much help tweaking your window treatments can be. Check out our guides to staying cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

How to make a rental more efficient

For folks who don’t own their homes, there are still plenty of simple updates that can curb an electric bill. From window treatments to HVAC filters, easy projects that won’t risk your lease can add up to a home that’s way less power hungry. (Of course, these tweaks also apply to anyone!). Here are nine tips for making a rental more energy efficient.

- Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS), U.S. Energy Information Administration ↩︎

- Electricity Consumption Variation of Public Buildings in Response to COVID-19 Restriction and Easing Policies: A Case Study in Scotland, U.K., Energy & Buildings, May 2022 ↩︎

- Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2022, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Apr. 2024 ↩︎

- Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS), U.S. Energy Information Administration ↩︎

- Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Jan. 2024 ↩︎

- Hawaii State Energy Profile, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Apr. 2024 ↩︎

- Louisiana, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Aug. 2024 ↩︎

- Understanding Electricity Consumption: A Comparative Contribution of Building Factors, Socio-Demographics, Appliances, Behaviours and Attitudes, Applied Energy, Sep. 2016 ↩︎

- Monthly Energy Review, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Jul. 2024 ↩︎